ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Wellcome Collection

Image source, Wellcome Collection

By Rachel Russell

BBC News

A museum in London is closing one of its main exhibitions following concerns over "racist, sexist and ableist theories and language".

The Wellcome Collection says the Medicine Man display will end on Sunday after a 15-year run.

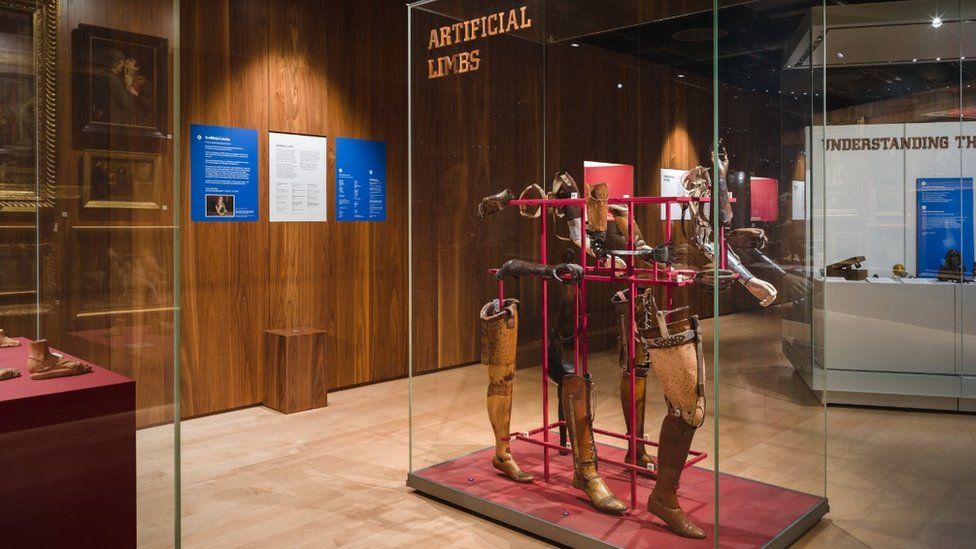

Founder Henry Wellcome, who died in 1936, collected more than a million objects to give an insight into global health and medicine.

The museum has marked the closure as a "significant turning point".

Controversial objects include a 1916 painting titled "A Medical Missionary Attending to a Sick African" which depicts an African person kneeling in front of a white missionary.

The museum said in a statement on Twitter: "We can't change our past. But we can work towards a future where we give voice to the narratives and lived experiences of those who have been silenced, erased and ignored.

"We tried to do this with some of the pieces in Medicine Man using artist interventions. But the display still perpetuates a version of medical history that is based on racist, sexist and ableist theories and language."

It added that exhibiting the collection of paintings, books and anatomical models told a colonial story of a man with "enormous wealth, power and privilege".

The statement continued: "The result was a collection that told a global story of health and medicine in which disabled people, Black people, Indigenous peoples and people of colour were exoticised, marginalised and exploited - or even missed out altogether."

The Wellcome Collection's website says a new exhibition featuring health stories of people who have been previously marginalised or even erased from museums will be unveiled in the coming years.

The museum brought in a new director called Melanie Keen in 2019, according to the Guardian.

She said at the time she wanted to address who the objects in the museum really belonged to and how they were acquired.

Ms Keen said: "It feels like an impossible place to be worrying about this material we hold without interrogating what it is, what narratives there are to be understood in a more profound way, and how the material came to be in our collection."

2 years ago

72

2 years ago

72

English (US) ·

English (US) ·