ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

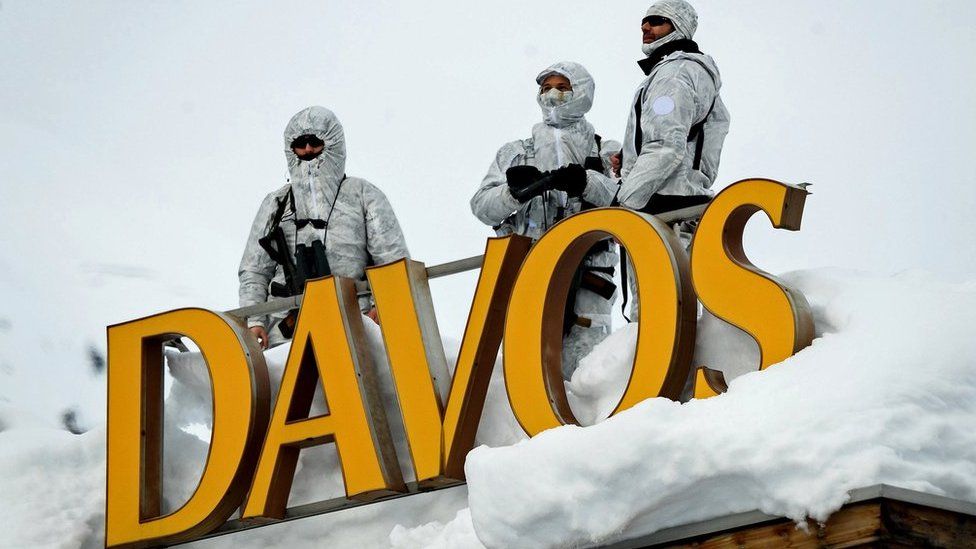

Security is tight at the Alpine event

By Faisal Islam

Economics editor

There has been a change of climate in the Alps this winter, and it's not just that the snow has finally fallen after an unseasonably warm December.

Chief executives and government ministers from around the globe are gathering for the annual World Economic Forum (WEF) in Davos, Switzerland, where for the last three years the focus has very much been on how to tackle the huge series of shocks that has hit the world economy.

From the wet market of Wuhan, to the Kremlin's crazed calculations, pandemic and war have conditioned a path of record inflation and surging debts, with a third of the world expected to be in recession this year.

But there is some light at the end of the tunnel. And however distant a ski resort full of global leaders may sound, WEF is the sort of place where you get a sense as to whether a three-year storm may start to subside.

There are some signs that the first indicators of surging inflation in the world economy are now beginning to normalise. Supply chains for the parts and ingredients that make the products we buy have been repaired after getting gummed up during the pandemic.

For example, Elon Musk's company Tesla attributed its decision to slash the prices of its electric cars last week to this shift. Shipping costs are tumbling. And China's "great reopening" after the pandemic - the end of strict zero-Covid lockdowns and restrictions - should, in theory, help the world economy, although the health costs of widespread infections might be so profound that it does not.

Around the world it seems that inflation, while high, has peaked. Incredibly, much of Europe has managed to end its dependence on Russian gas within the space of a year, constructing temporary terminals to process shipped liquid gas so it doesn't have to rely on pipelines from Siberia.

Image source, Getty Images

Green trade war?

However, there are also newer tensions emerging, raising questions about how far inflation will eventually fall, and some concern about where Britain sits in a much changed world.

The big shadow here is the threat of a transatlantic green trade war. Joe Biden's new legislation to boost America's green economy includes £300bn of subsidies for the purchase of electric cars, but only if they are mainly manufactured in North America. The Inflation Reduction Act also affects a swathe of other manufacturing and production and is persuading some European companies to relocate factories to the US. Even fertiliser companies are having their heads turned and wondering why European leaders aren't bringing in similar laws.

The US suggests its new legislation is aimed at competing with China. But EU leaders are furious and about to respond, potentially with significant subsidies of their own, presumably also containing "Buy European" clauses.

If the three major trade blocks try to out-subsidise each other, what should "global Britain" do? The "globe" that Britain tried to "re-engage" with after Boris Johnson's post-Brexit break with Europe's single market is really rather different now.

Would EU "buy European" strictures include the UK? The government has expressed some concerns in a letter to the White House, but it is unclear what Britain's strategy is, or if there is one. It isn't just about low carbon manufacturing either. Similar dynamics - an attempted US-EU carve-up - are also apparent in the recent drive to re-shore production of microchips from east Asia.

This new divided Davos backdrop to the global economy could have profound consequences for how much things cost, and where they are made. It is a precise reversal of the consensus seen at the World Economic Forum for decades. Things are very much up for grabs here.

And lastly, many corporate leaders seem to have spent their Christmases being shocked by the cost-saving potential of the new artificial intelligence platform ChatGPT 3. There is a school of thought that the next iteration of this technology from OpenAI - ChatGPT 4 - could be so impactful as to cause a global economic shock. It will be a quantum leap for technology, but at the expense of making millions of existing jobs redundant.

With war in Europe, China reopening, and a long anticipated technological revolution occurring, policy and investment decisions will be made at Davos this week that could change the direction of the world economy, and so impact us all profoundly.

2 years ago

52

2 years ago

52

English (US) ·

English (US) ·