ARTICLE AD BOX

BBC

BBC

The accused mastermind of the 9/11 terror attacks on the US will no longer plead guilty on Friday, after the US government moved to block plea deals reached last year from going ahead.

Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, often referred to as KSM, was due to deliver his pleas at a war court on the Guantanamo Bay naval base in southeastern Cuba, where he has been held in a military prison for almost two decades.

Mohammed is Guantanamo's most notorious detainee and one of the last held at the base.

But a federal appeals court on Thursday evening halted the scheduled proceedings to consider requests from the government to abandon plea deals, which it said would cause "irreparable" harm to both it and the public.

A three-judge panel said the delay "should not be construed in any way as a ruling on the merits", but was aimed at giving the court time to receive a full briefing and hear arguments "on an expedited basis".

The delay means that the matter will now fall into the incoming Trump administration.

What was scheduled to happen this week?

At a hearing beginning on Friday morning, Mohammed was scheduled to plead guilty to his role in the 11 September 2001 attacks, when hijackers seized passenger planes and crashed them into the World Trade Center in New York and the Pentagon outside of Washington. Another plane crashed into a field in Pennsylvania after passengers fought back.

Mohammed has been charged with offences including conspiracy and murder, with 2,976 victims listed on the charge sheet.

He has previously said that he planned the "9/11 operation from A-to-Z" - conceiving the idea of training pilots to fly commercial planes into buildings and taking those plans to Osama bin Laden, leader of the militant Islamist group al-Qaeda, in the mid 1990s.

Friday's hearing was scheduled to happen in a courtroom on the base, where family members of those killed and the press would have been seated in a viewing gallery behind thick glass.

Why is this all happening 23 years after 9/11?

Pre-trial hearings, held at a military court on the naval base, have been going on for more than a decade, complicated by questions over whether torture Mohammed and other defendants faced while in US custody taints the evidence.

Following his arrest in Pakistan in 2003, Mohammed spent three years at secret CIA prisons known as "black sites" where he was subjected to simulated drowning, or "waterboarding", 183 times, among other so-called "advanced interrogation techniques" that included sleep deprivation and forced nudity.

Karen Greenberg, author of The Least Worst Place: How Guantanamo Became the World's Most Notorious Prison, says the use of torture has made it "virtually impossible to bring these cases to trial in a way that honors the rule of law and American jurisprudence".

"It's apparently impossible to present evidence in these cases without the use of evidence derived from torture. Moreover, the fact that these individuals were tortured adds another level of complexity to the prosecutions," she says.

The case also falls under the military commissions, which operate under different rules than the traditional US criminal justice system and slow the process down.

A plea deal was struck last summer, following some two years of negotiations.

What does the plea deal include?

The full details of the deals reached with Mohammed and two of his co-defendants have not been released.

We do know that a deal means he would not face a death penalty trial.

In a court hearing on Wednesday, his legal team confirmed that he had agreed to plead guilty to all charges. Mohammed did not address the court personally, but engaged with his team as they went over the agreement, making small corrections and changes to wording with the prosecution and the judge.

If the deals are upheld and the pleas are accepted by the court, the next steps would be appointing a military jury, known as a panel, to hear evidence at a sentencing hearing.

In court on Wednesday, this was described by lawyers as a form of public trial, where survivors and family members of those killed would be given the opportunity to give statements.

Under the agreement, the families would also be able to pose questions to Mohammed, who would be required to "answer their questions fully and truthfully", lawyers say.

Central to the prosecution agreeing to the deals was a guarantee "that we could present all of the evidence that we thought was necessary to establish a historical record of the accused's involvement in what happened on September 11th," prosecutor, Clayton G. Trivett Jr., said in court on Wednesday.

Even if the pleas go ahead, it would be many months before these proceedings would begin and a sentence ultimately delivered.

Reuters

Reuters

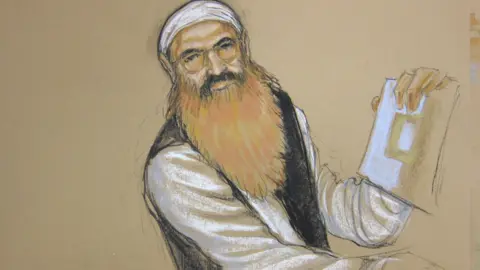

The case against Khalid Sheikh Mohammed, shown here during a 2012 pre-trial hearing, has been ongoing for two decades at the U.S. Naval Base Guantanamo Bay.

Why is the US government trying to block the pleas?

US Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin appointed the senior official who signed the deal. But he was travelling at the time it was signed and was reportedly caught by surprise, according to the New York Times.

Days later, he attempted to revoke it, saying in a memo: "Responsibility for such a decision should rest with me as the superior authority."

However, both a military judge and a military appeals panel ruled that the deal was valid, and that Mr Austin had acted too late.

In another bid to block the deal, the government this week asked a federal appeals court to intervene.

In a legal filing, it said Mohammed and the two other men were charged with "perpetrating the most egregious criminal act on American soil in modern history" and that enforcing the agreements would "deprive the government and the American people of a public trial as to the respondents' guilt and the possibility of capital punishment, despite the fact that the Secretary of Defense has lawfully withdrawn those agreements".

Following the announcement of the deal last summer, Republican Senator Mitch McConnell, then the party's leader in the chamber, released a statement describing it as "a revolting abdication of the government's responsibility to defend America and provide justice".

What have the victims' families said?

Some families of those killed in the attacks have also criticised the deal, saying it is too lenient or lacks transparency.

Speaking to the BBC's Today Programme last summer, Terry Strada, whose husband Tom was killed in the attacks, described the deal as "giving the detainees in Guantanamo Bay what they want".

Ms Strada, the national chair of the campaign group 9/11 Families United, said: "This is a victory for Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and the other two, it's a victory for them."

Other families see the agreements as a path towards convictions in the complex and long-running proceedings and were disappointed by the government's latest intervention.

Stephan Gerhardt, whose younger brother Ralph was killed in the attacks, had flown to Guantanamo Bay to watch Mohammed plead guilty.

"What is the end goal for the Biden administration? So they get the stay and this drags into the next administration. To what end? Think about the families. Why are you prolonging this saga?" he said.

Mr Gerhardt told the BBC the deals were "not a victory" for the families, but that it was "time to find a way to close this, to convict these men".

Families on the base were meeting with the press when news of the delay was made public.

"It was supposed to be a time of healing. We'll board that plane still with that deep sense of pain – there's just no end to it," one said.

Why are the proceedings happening in Guantanamo?

Mohammed has been held in a military prison in Guantanamo Bay since 2006.

The prison was opened 23 years ago - on 11 January 2002 - during the "war on terror" that followed the 9/11 attacks, as a place to hold terror suspects and "illegal enemy combatants".

Most of those held here were never charged and the military prison has faced criticism from rights groups and the United Nations over its treatment of detainees. The majority have now been repatriated or resettled in other countries.

The prison currently holds 15 - the smallest number at any point in its history. All but six of them have been charged with or convicted of war crimes.

6 days ago

8

6 days ago

8

English (US) ·

English (US) ·