ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, NASA

Image source, NASA

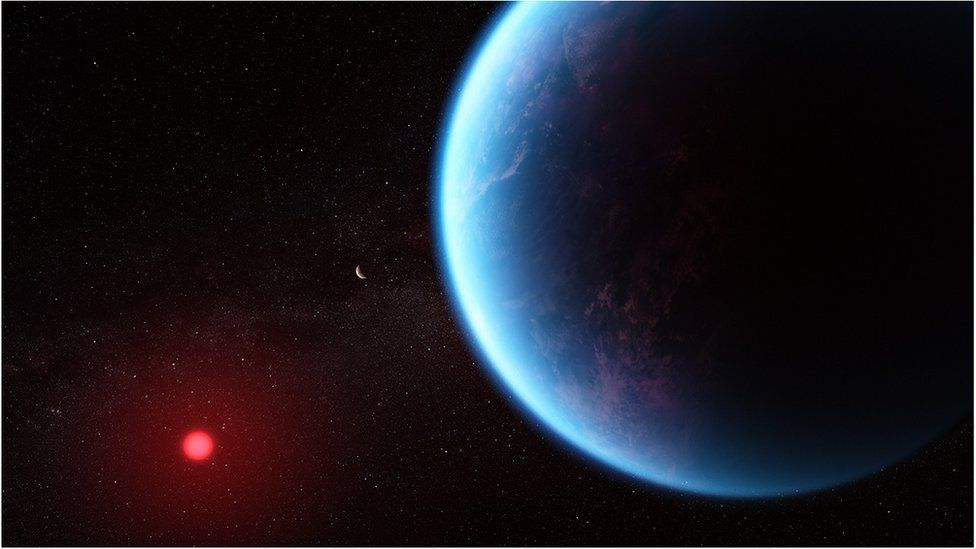

Artwork: K2-18 b orbits a cool dwarf star shown in red just far enough away for its temperature to support life.

By Pallab Ghosh

Science correspondent

Nasa's James Webb Space Telescope may have discovered tentative evidence of a sign of life on a faraway planet.

It may have detected a molecule called dimethyl sulphide (DMS). On Earth, at least, this is only produced by life.

The researchers stress that the detection on the planet 120 light years away is "not robust" and more data is needed to confirm its presence.

Researchers have also detected methane and CO2 in the planet's atmosphere.

It's the first time these gasses have been found in a planet outside our solar system and could mean the planet, named K2-18b, has a water ocean.

Prof Nikku Madhusudhan, of the University of Cambridge, who led the research, told BBC News that his entire team were ''shocked'' when they saw the results.

"On Earth, DMS is only produced by life. The bulk of it in Earth's atmosphere is emitted from phytoplankton in marine environments," he said.

Caution

But Prof Madhusudhan described the detection of DMS as tentative and said that more data would be needed to confirm its presence. Those results are expected in a year.

''If confirmed, it would be a huge deal and I feel a responsibility to get this right if we are making such a big claim.''

It is the first time astronomers have detected the possibility of DMS in a planet orbiting a distant star. But they are treating the results with caution, noting that a claim made in 2020 about the presence of another molecule, called phosphine, that could be produced by living organisms in the clouds of Venus were disputed a year later.

Even so, Dr Robert Massey, who is independent of the research and deputy director of the Royal Astronomical Society in London, said he was excited by the results.

''We are slowly moving towards the point where we will be able to answer that big question as to whether we are alone in the Universe or not," he said.

''I'm optimistic that we will one day find signs of life. Perhaps it will be this, perhaps in 10 or even 50 years we will have evidence that is so compelling that it is the best explanation.''

JWST is able to analyse the light that passes through the faraway planet's atmosphere. That light contains the chemical signature of molecules in its atmosphere. The details can be deciphered by splitting the light into its constituent frequencies - rather like a prism creating a rainbow spectrum. If parts of the resulting spectrum are missing, it has been absorbed by chemicals in the planet's atmosphere, enabling researchers to discover its composition.

Image source, ESA

Image caption,Artwork: The James Webb Space Telescope is capable of analysing tiny flecks of light from the atmospheres of distant planets

The feat is all the more remarkable because the planet is more than 1.1 million billion km away, so the amount of light reaching the space telescope is tiny.

As well as DMS, the spectral analysis detected an abundance of the gasses methane and carbon dioxide with a good degree of confidence. This is the first time that these gasses have been detected around a planet orbiting a star other than our Sun. That in itself is an enormous scientific achievement.

The proportions of CO2 and methane are consistent with there being a water ocean underneath a hydrogen-rich atmosphere. Nasa's Hubble telescope had detected the presence of water vapour previously, which is why the planet, which has been named K2-18b, was one of the first to be investigated by the vastly more powerful JWST, but the possibility of an ocean is a big step forward.

Recipe for life

The ability of a planet to support life depends on its temperature, the presence of carbon and probably liquid water. Observations from JWST seem to suggest that that K2-18b ticks all those boxes. But just because a planet has the potential to support life it doesn't mean that it does, which is why the possible presence of DMS is so tantalising.

What makes the planet even more intriguing is that it is not like the Earth-like, so called rocky planets, discovered orbiting distant stars that are candidates for life. K2-18b is nearly nine times the size of Earth.

Exoplanets - which are planets orbiting other stars - which have sizes between those of Earth and Neptune, are unlike anything in our solar system. This means that these 'sub-Neptunes' are poorly understood, as is the nature their atmospheres, according to Dr Subhajit Sarkar of Cardiff University, who is another member of the analysis team.

"Although this kind of planet does not exist in our solar system, sub-Neptunes are the most common type of planet known so far in the galaxy," he said.

"We have obtained the most detailed spectrum of a habitable-zone sub-Neptune to date, and this allowed us to work out the molecules that exist in its atmosphere."

1 year ago

44

1 year ago

44

English (US) ·

English (US) ·