ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Telegram

Image source, Telegram

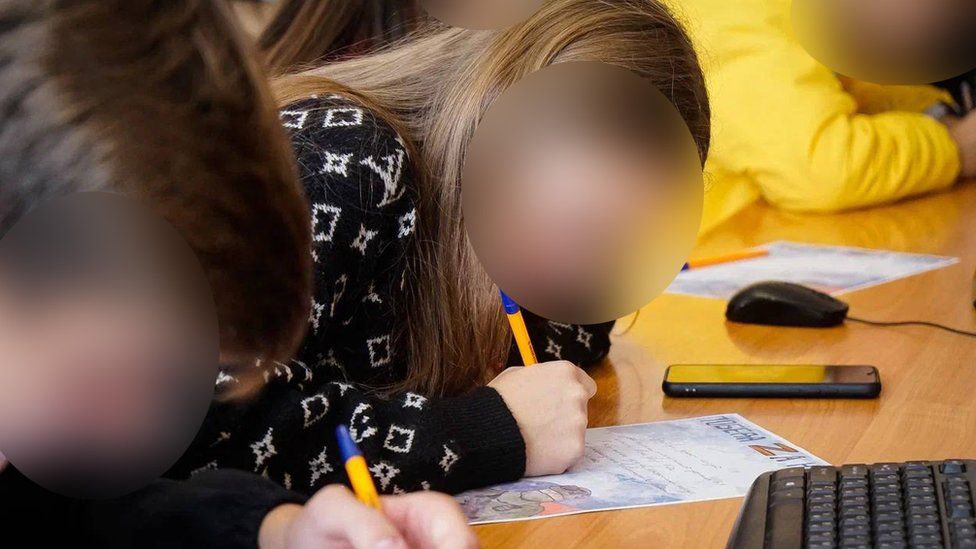

Children at school in Russian-occupied Ukraine (not the school featured in this report), writing "letters of support" to Russian soldiers

By Anastasiia Levchenko

BBC News, Kyiv

Like millions of other Ukrainians, in the early weeks of Russia's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Nataliia (not her real name) was forced from her home.

She couldn't tolerate living under Russian occupation in her southern hometown of Melitopol, and felt she would be more useful in territory still controlled by Ukraine.

But Nataliia didn't just leave her home and relatives behind, she also surrendered her profession, giving up her job of 20 years as a teacher.

Now she spends her time giving online classes to hundreds of her former students.

The risks for her, and her remote class, are huge.

False names

"No-one had done this before," Nataliia explains to us. "Not in Crimea, or in the occupied Donbas, Kherson or the Zaporizhzhia regions."

Portraits of Vladimir Putin now hang on the walls of Nataliia's old classrooms in Melitopol. The pupils must both learn, and sing, the Russian national anthem. They are even obliged to write "inspirational letters" to Russian soldiers.

This is how Ukrainian children are educated in territories occupied by Russia. They are taught that Ukraine isn't a real country - and Nataliia says, if a child challenges the curriculum, their parents are threatened with beatings or torture.

It's why Nataliia, with her former colleagues, created an online teaching platform to try to "save the minds of Ukrainian children".

"Once we launched it, I wrote a neutral letter, offering the classes to all of the parents," explains Nataliia. "I didn't know who was pro-Ukrainian or pro-Russian, and they knew my home address and my relatives".

She says even uttering the word "occupation" can result in Russian authorities visiting your home. If there is any evidence of loyalty to Ukraine, such as a child's homework being written in Ukrainian instead of Russian, a trip to the police station could follow.

And yet, hundreds of families have taken up Nataliia's offer to teach the Ukrainian curriculum - and numbers are growing.

In the morning, they attend Russian school, and in the afternoon or evening, the pupils have secret online lessons with Ukrainian teachers.

Image source, Telegram

Image caption,Students at school in Russian-occupied Ukraine (not the school featured in this report), standing next to a screen which says, ‘Homewards to Russia’

"Safety is more important than knowledge. All the students join with their cameras off and use false nicknames," says Nataliia.

Recordings are provided for those who might not have a signal or power.

"It's not so important to teach children what year Taras Shevchenko [a famous Ukrainian poet] was born, or the rules of geometry, but to keep them connected with Ukrainian culture," she explains.

"I have one student who came home and cried after the Russian lessons. This is too much psychological pressure for a child. All their lives they lived in a Ukrainian environment - and suddenly, everything changed."

Valera (not his real name) goes to a Russian school but also attends online Ukrainian classes. The 14-year-old told us only six out of his 31 classmates support Ukraine. He says he tries to resist Russification when he can.

"Once we turned on the Ukrainian anthem during our lesson, on the phone," he recalls. "Then they started to search everyone. I hid my phone; once they played their anthem - everyone stood up, we remained seated."

He says he always wanted this additional Ukrainian teaching, but Valera believes he is going to be made to join the Russian army.

Nataliia concedes the purpose of her teaching is constantly tested. The longer Russia occupies Melitopol, the greater the risk children living there will be indoctrinated.

"I can't check their homework normally," she says. "I fear for our future generation. It's very important to keep these children connected to reality. But it is so difficult to do."

Additional reporting by Joyce Liu

10 months ago

66

10 months ago

66

English (US) ·

English (US) ·