ARTICLE AD BOX

By Pallab Ghosh

Science correspondent

Image source, Cern

Image source, Cern

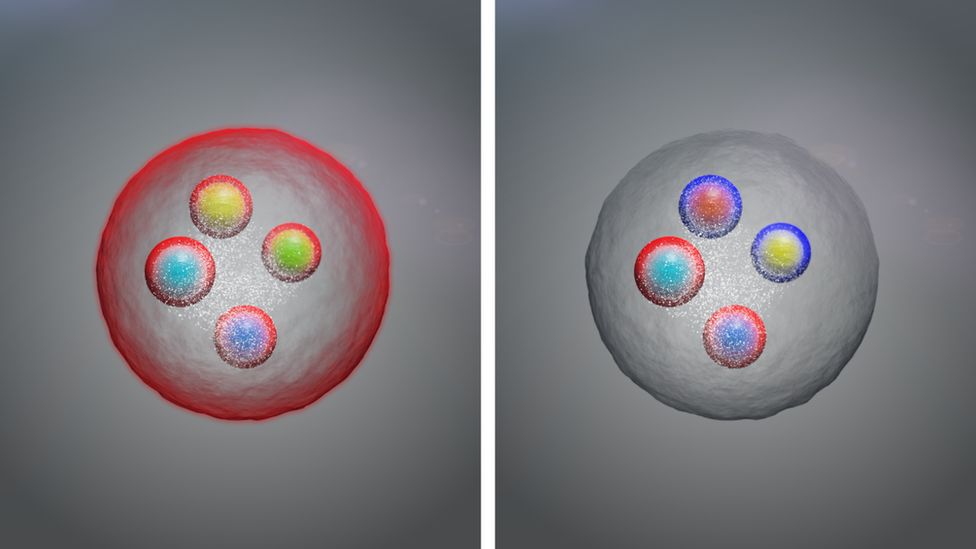

"Exotic" states of matter exist for less than a blink of an eye

Scientists have found new ways in which quarks, the tiniest particles known to humankind, group together.

The new structures exist for just a hundred thousandth of a billionth of a billionth of a second but may explain how our Universe is formed.

Atoms contain smaller particles called neutrons and protons, which are made up of three quarks each.

"Exotic" matter discovered in recent years is made up of four and five quarks - tetraquarks and pentaquarks.

Scientists at the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland have discovered one new pentaquark and two tetraquarks. This takes the total number discovered there to 21. Each is unique, but researchers are excited about the qualities of the three new finds.

The new pentaquark decays into particles that none of the others produce, while the two tetraquarks have the same mass, suggesting they may be the first known pair of exotic structures.

Perhaps even more importantly, though, the latest finds mean that there are now enough of these particles to begin grouping them together, like the chemical elements in the periodic table. That is an essential first step towards creating a theory and set of rules governing exotic mass.

In light of the new discoveries, physicists are discussing this very issue at a special seminar on Tuesday at CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research, which houses the Large Hadron Collider.

Working out miniscule differences between the tiniest things we know about may seem arcane, but the interaction of quarks creates the so-called "strong force" that holds the insides of atoms - and by extension our entire Universe - together.

"The strong force is extremely difficult to calculate, and we don't have firm predictions of how the exotic pentaquarks and tetraquarks are built," says Prof Chris Parkes of Manchester University. "But we hope that by finding out about them we can develop theories that enable us to understand them better."

What are quarks?

A Greek philosopher, Democritus, put forward the idea in the fifth century that the world was made up of indivisible particles which he called atoms.

By the end of the 19th and early 20th century, experimental results showed that atoms were made up of smaller particles: electrons, neutrons and protons.

And in the 1960s, it became clear that neutrons and protons themselves were made from smaller particles still, called quarks; and that the interaction of quarks was tied to one of the fundamental forces of nature called the strong force.

The force not only holds the insides of atoms together, but is important in the interactions of other sub-atomic particles that make the Universe tick.

The Large Hadron Collider has undergone a major upgrade and the researchers involved believe that they will discover many more such exotic particles, some of which may have six quarks bound together.

Some of these may have a less fleeting existence - perhaps a hundred billionth of a second. That is brief by human standards, but because these particles travel at the speed of light, they would leave trails a few millimetres long, which would be a treasured footprint for physicist sleuths to follow.

Related Internet Links

The BBC is not responsible for the content of external sites.

2 years ago

33

2 years ago

33

English (US) ·

English (US) ·