ARTICLE AD BOX

Will Grant

BBC News

Reporting fromTijuana, Mexico

BBC

BBC

Humanitarian tents set up outside the US-Mexico border

Shivering a little, Marcos pulls his hoodie over his head as much to protect his identity as to shield him from the cold.

A year ago, at just 16 years old, he says he was forcibly recruited into a drug cartel in his home state of Michoacán, Mexico.

Recounting his story of horror and escape, Marcos (not his real name) says he and his family fled Michoacán with only what they were wearing.

Leaving for the pharmacy one evening to buy painkillers for his mother's toothache, he says he was suddenly surrounded by four pick-up trucks with armed men inside.

"Get in," he says they ordered, "or we'll kill your family."

They dragged him off to a shack where several other youths were in the same predicament, according to Marcos.

For months, he says he was made to be a foot soldier in a war he wanted no part of, before managing to escape with the help of a gang member who took pity on him.

Marcos has spent months inside a migrant shelter in the Mexican border city of Tijuana waiting to make his case for asylum before the US authorities, confident that he could convince them he has what US immigration courts call "credible fear" of persecution or torture in Mexico.

But now he thinks President Trump's sweeping executive orders on immigration and border security have ruined his chances of success.

"I hope they look at the circumstances of every person and take each case on its merit," he says, "and that Mr Trump's heart softens to help those who truly need it."

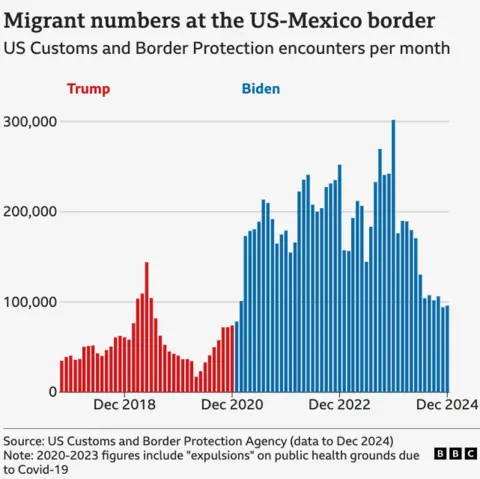

From the Oval Office on Monday evening, hours after returning to the presidency, Trump signed a blizzard of orders aimed at delivering on one of his central campaign promises: to drastically reduce illegal migration and asylum claims at the US border.

Among the measures were a move to declare some drug cartels terrorist organisations, paving the way for US military action and deportations.

That order has Pastor Albert Rivera, the director of a migrant shelter that primarily houses people fleeing cartel intimidation and death threats, confused.

He says there's a contradiction at the heart of the executive order.

"If you're going from saying these people are fleeing gangs to say they are now fleeing terrorists, surely that only makes their claims for asylum stronger," he argues.

For Trump's supporters on the other side of the border, in southern California, the need for these strict new measures is self-evident.

"It will be a relief," says Paula Whitsell, the chairwoman of the San Diego County Republican Party, about the new president's plan to launch what he's called "the largest deportation in American history".

"Our system here in San Diego County is very burdened by the heavy weight of all these people coming in, and we're just not built for it. The county is not made to be able to sustain this," she argues.

She insists the measures are not inherently anti-immigrant – "we are still a nation of immigrants" – but directed instead at removing undocumented criminals in the US and dismantling the gangs that operate people-smuggling routes across the border.

But for people waiting in Mexico, who say they have done nothing wrong and have legitimate claims for asylum, Trump's orders have had sweeping and swift consequences.

On the morning that the president took the oath of office, around 60 migrants gathered at the Chaparral crossing in Tijuana, waiting to speak to border guards about their asylum claims. But they never got the chance, as Mexican officials instead directed them towards buses that would take them back to shelters.

The CBP One app - a mobile application launched by the Biden administration and criticised by Trump on the campaign trial - had shut down.

The app had been the only legal pathway to request asylum at the US-Mexico border, and with all of its appointments scrapped, there would no crossing the border.

For some, it felt like the end of the road.

Oralia has been living with her two youngest children for seven months in a nylon tent just walking distance from the US border.

She says she is also fleeing cartel threats in Michoacán, and that her 10-year-old boy has epilepsy. She says her hope was to get him medical attention somewhere safe in the US.

But without the CBP One app, Oralia says she has little hope that her claim will ever be heard.

"We have no choice but to go back and trust in God that nothing happens," she says.

A local migrant rights' lawyer has apparently advised her to wait and see how President Trump's actions unfold. But Oralia's mind is made up.

Her bags packed, the tent she's called home for most of the last year is now vacant for the next family.

"It's all been so unjust," she says, wiping away tears.

"Mexico receives their citizens with no complaint, but it doesn't work the other way round.

"I just hope God moves him [Trump] because there are lots of families like ours."

4 months ago

26

4 months ago

26

English (US) ·

English (US) ·