ARTICLE AD BOX

By Geeta Pandey

BBC News, Delhi

Image source, Courtesy of Netflix

Image source, Courtesy of Netflix

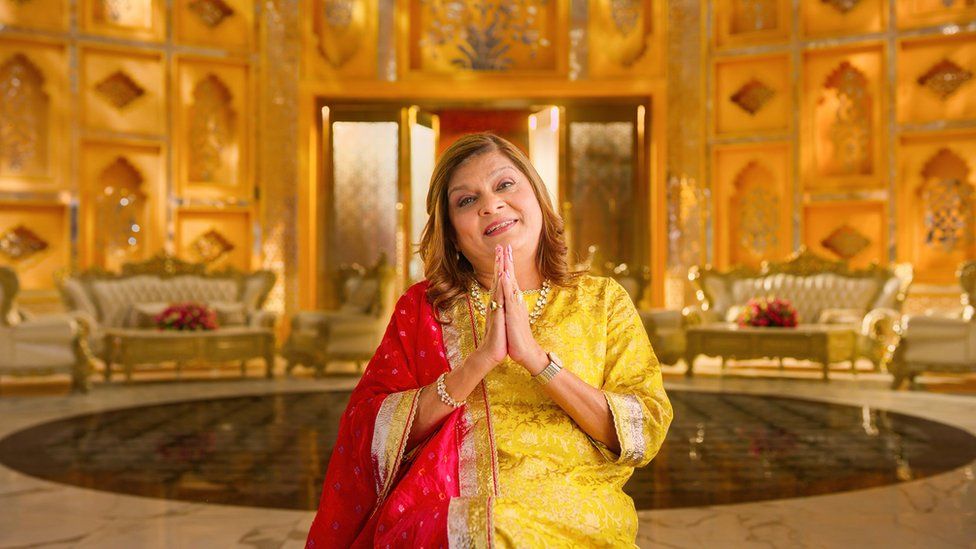

Sima Taparia, popularly known as "Sima aunty", claims to be "Mumbai's top matchmaker"

Indian Matchmaking - the "cringeworthy" Netflix show that created a huge buzz in India and many parts of the globe two years ago - is back with a second season. It has once again renewed the debate about whether the show is regressive or if it holds up a mirror to society.

The eight-part reality TV show - included in the list of the 50 most influential reality TV shows of all time by Time magazine - once again follows elite Indian matchmaker Sima Taparia as she tries to find suitable matches for her wealthy clients in India and the US.

Here, everything happens for a reason - and that is to find a bride or a groom because, as Ms Taparia explains at the outset, "first is marriage, then love" and "everything gets adjusted after marriage".

The new season includes some of her old clients from season one and a number of new faces, hoping that Ms Taparia, who claims to be "Mumbai's top matchmaker", will help them find "The One".

To many, the faith these rich and successful millennials put in the matchmaker - popularly known as "Sima aunty" - may seem questionable, considering none of her matches from the previous season worked out.

But that's not the only thing questionable about Sima aunty - or the show.

Despite its immense popularity, season one was called out for in-your-face misogyny, casteism and colourism and caused much outrage, with many describing it as regressive.

Image source, Courtesy of Netflix

Image caption,The show has been called out for being regressive and perpetuating biases and outdated ideas

In the new season, the matchmaker's edges are softened a bit and she seems to be holding her tongue sometimes - possibly because of the backlash - but the show is still riddled with sexism and gender biases. She's still nicer to men - they are "good boys" while women are "inflexible" or "difficult" or even "superficial".

So Akshay, a male client who calls himself the "world's most eligible bachelor", is allowed to call women "chicks" and the female clients are routinely told to temper their expectations. "You won't get 100%," she keeps reminding them, adding that "60-70%" is a reasonable expectation.

The show has also made headlines in India over Ms Taparia's controversial comment on age difference - she tells a female client that her relationship with a man who is seven years younger is not a good match, "just like that of Priyanka Chopra and Nick Jonas".

Critics also accuse the series of promoting stereotypes and say it makes no effort at diversity.

"It represents only one kind of people," says Shailaja Bajpayee, editorial adviser to The Print website. "They are all rich, upper-caste and fair-skinned people. There are no lower castes or religious minorities, except for one Sikh, and I can't remember seeing anyone who has darker skin colour."

Despite the criticism, the series was among the top five shows in India for two weeks since its launch on 10 August. It was also among the top 10 in 13 countries, including in the US, Canada and South Africa, in the first week of its release and remained on the list in seven countries for another week.

Image source, Courtesy of Netflix

Image caption,The second season does see a wedding - but it is not arranged by Ms Taparia

Thousands have taken to social media to share their impressions of the show. And it has already been renewed for season three which will focus on matchmaking in the UK.

Film and trade analyst Komal Nahata says the interest in the show is because season one was "a huge and roaring success - not just among Indians but also in the US and several other countries".

"For people in the West, where most go to Tinder and Bumble and other websites to find matches, the show had shock value. This type of matchmaking that we have in India is very unique and Westerners couldn't believe that it actually happens like this," he told the BBC.

In India too - where 90% of all marriages are still arranged - there's growing interest in professional matchmaking, at least in cities and towns.

"Gone are the days when uncles and aunts and other relatives would suggest a match," Mr Nahata says. "Because of the growing number of divorces, relatives - or even parents - do not want to get involved, so that they don't get blamed if a marriage doesn't work out. So, matchmakers have proliferated, they are everywhere."

Ms Bajpayee says that people go to matchmakers "because it's not easy to find a match, and sometimes you need a bit of help", but adds that there are a lot of problems with the show as "it's still not critiquing regressive ideas" and "just propagates known biases".

"What I found most odd was that all these women in the US - who are educated and independent and are free to marry whoever they want to - still seek out someone like Ms Taparia. And they're all looking for matches from the same background as in caste and religion. You have one woman saying she doesn't just want a Gujarati match, but that he also must speak Gujarati.

"It made me sad to think that all these women have learnt nothing from living all these years in America," she adds.

Image source, Courtesy of Netflix

Image caption,Ms Taparia has been criticised for being gender biased

In an interview with Variety last week, Smriti Mundhra, the show's creator, agreed that "some of the show is cringey".

"Some of the things we do and say and believe and have internalised over generations are cringey. It's difficult to face those topics of conversations; it's difficult to see that reflected back at you."

But, she added, that by raising difficult topics, the series provided families an opportunity to have "tough conversations".

But Sreemoyee Piu Kundu, author and founder of Status Single, India's first and only community for urban single women, questions the rationale behind promoting a show on weddings in India "where women are judged all the time for not getting married".

"Indians have a national obsession with marriage, and it's a very unhealthy obsession. And this show is a hard-sell of a patriarchal construct - that marriage is a be-all and end-all."

It's especially absurd, she says, in a country where thousands of brides are killed every year over insufficient dowry, marital rape is not criminalised and thousands of housewives are driven to suicide every year.

"I want to ask Netflix why are you putting your money into a show that propagates mass misogyny? Why not have a show on single women?" she asks, adding that "marriage is not the benchmark for our lives."

2 years ago

23

2 years ago

23

English (US) ·

English (US) ·