ARTICLE AD BOX

By Esme Stallard

BBC News

Image source, ITV

Image source, ITV

Love Island contestants are dressing in second-hand clothes, to make the new series "more eco-friendly".

But what are the environmental issues around fashion, and how much difference do pre-worn clothes make?

What is fast fashion?

Announcing the second-hand policy, Love Island producers said that UK shoppers were increasingly concerned about fast fashion.

The term describes the quick turnover of fashion trends and the move towards cheap, mass-produced clothing - with new lines constantly released.

This has resulted in wardrobes which are "overflowing with clothes", argues fast fashion campaigner Elizabeth Cline. Oxfam research suggests the average Briton has 57 unworn items.

Who buys fast fashion?

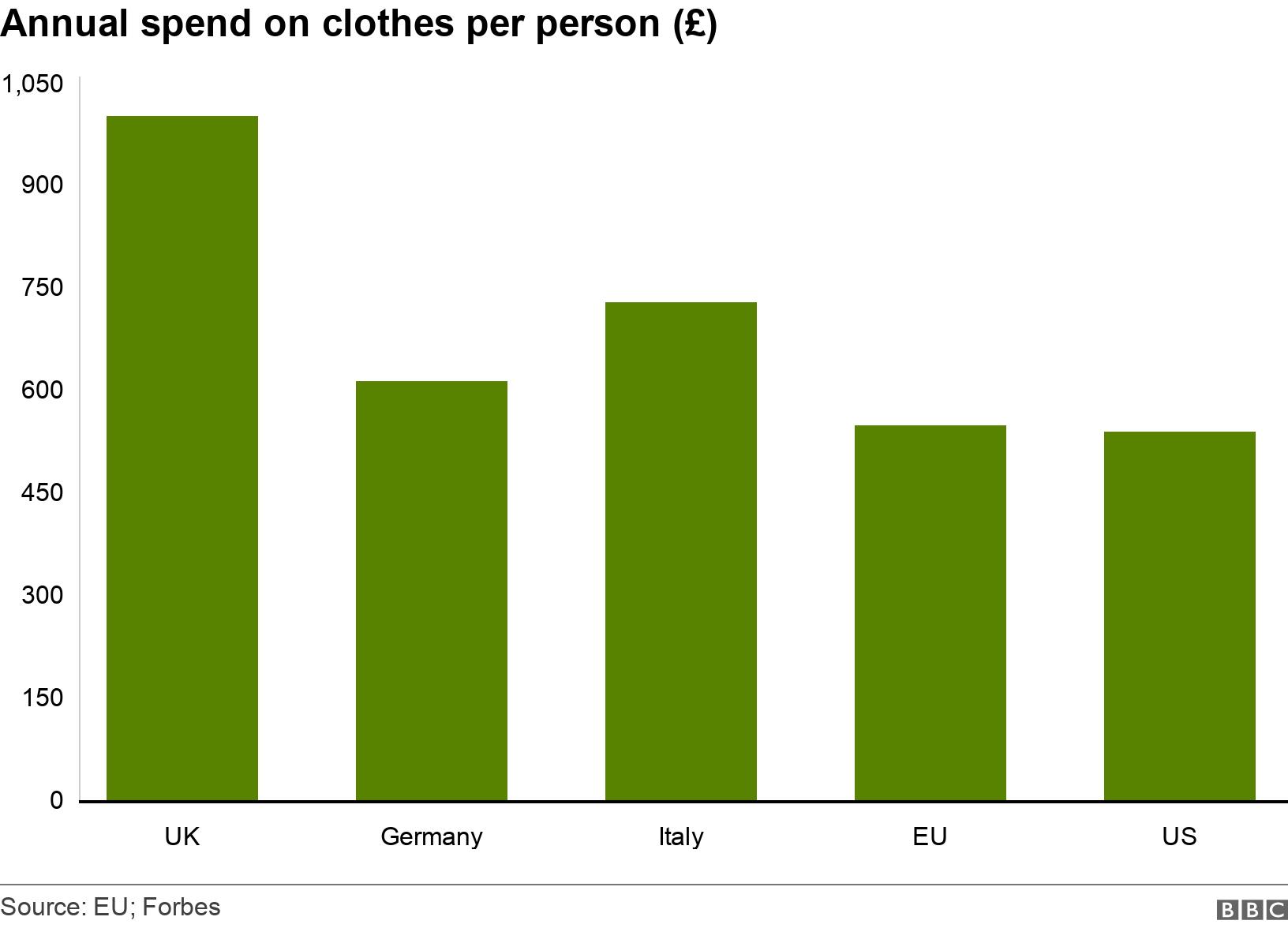

UK shoppers buy more clothes per person than those in any other country in Europe, according to MPs.

A recent survey by environmental charity Hubbub found that more than two-fifths of 16 to 24-year-olds buy clothes online at least once a week, compared to 13% on average for other age groups.

Research by Barclays bank in 2017 found that the men it surveyed spent nearly 25% more a month than women on clothes, although it looked at shopping in general, not just fast fashion.

What's the environmental impact of fast fashion?

Producing clothes uses a lot of natural resources and creates a significant amount of greenhouse gas emissions which are responsible for climate change.

Overall, the fashion industry is responsible for 8-10% of global emissions, according to the UN - more than the aviation and shipping sectors combined.

And global clothes sales could increase by up to 65% by 2030, the World Bank suggests, partly because of the continuing growth in online shopping.

Most of fashion's environmental impact comes from the raw materials used to make clothes:

The industry also uses a lot of water.

The UN has launched the #ActNow Fashion Challenge to highlight how industry and individuals can help improve fashion's environmental impact.

It says that reducing the fashion industry's carbon footprint "is key to limiting [global] warming".

Make clothes more sustainably

Several firms have launched "eco" collections which use organic and recycled materials, including H&M Conscious, Adidas x Parley and Zara Join Life.

But critics argue such collections don't solve the main problem of fast fashion: the promotion of overconsumption.

"Until brands tackle this issue first and foremost, 'conscious collections' by fast fashion brands can only ever be considered greenwashing," argues Flora Beverley, co-founder of sustainable brand Leo's Box.

Zara rejected the accusation, telling the BBC that it "does not use advertising to push demand or promote overconsumption". Adidas said that by 2025, "9 out of ten Adidas articles will be sustainable". H&M declined to comment.

Many "slow fashion" companies are emerging - offering fewer new pieces a year, all of which have a lower environmental impact.

But not everybody is prepared to pay for them.

A third of young people surveyed by the London Fashion Retail Academy said they wouldn't pay more than £5 extra for sustainable garments.

Image source, Getty Images

Charity shops and jumble sales have long offered a reliable way to extend the life of clothes. Online sites like eBay and Facebook Marketplace also make it easier to buy and sell pre-loved items.

But this doesn't necessarily mean that shoppers buy fewer items overall.

The waste charity Wrap argues that second-hand purchases are unlikely to replace more than 10% of new sales. It recommends other approaches, such as encouraging people to repair and revamp existing pieces.

Image source, Michael M. Santiago via Getty Images

Image caption,Rent the Runway has offered a rental service for clothes since 2009

Hiring clothes is another way to access new pieces.

Wrap argues that if renting replaced 10% of new purchases every year, it would save 160,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide in the UK alone.

The simplest solution could also be the most most effective.

Buying a maximum of eight new items a year could reduce fashion's emissions by 37% in the world's major cities, according to research by Leeds University and Arup.

But this would obviously have significant financial implications for manufacturers and retailers, a tension which is not unique to the fashion industry.

2 years ago

69

2 years ago

69

English (US) ·

English (US) ·