ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

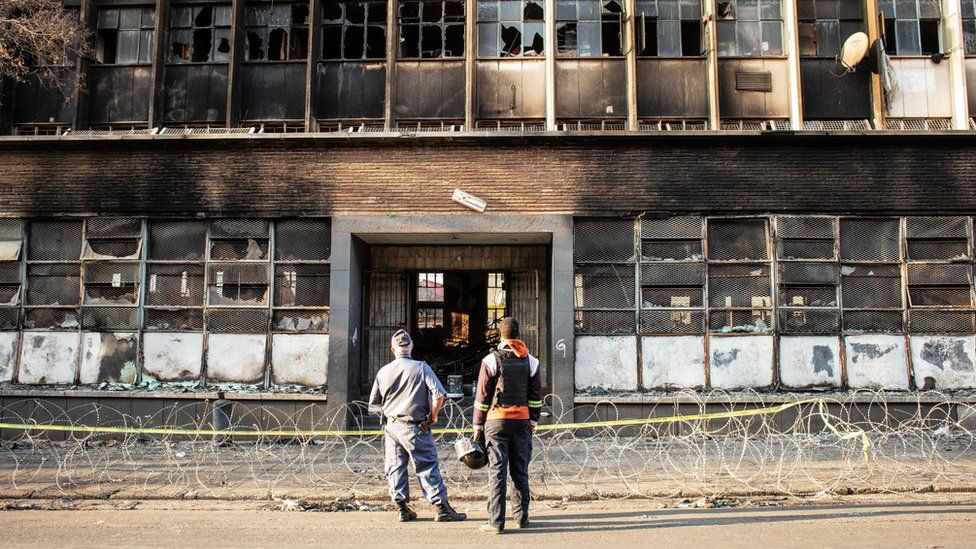

The building was home to some of South Africa's poorest people

By Daniel De Simone

BBC News, Johannesburg

The man was thought to be a witness, not a suspect.

But when he appeared this week at the public inquiry into South Africa's deadliest building fire, he announced he had started it.

The 29-year-old man, who cannot yet be publicly identified, said he started the fire in the Usindiso building last August unintentionally.

He described himself as working for a violent drug dealer who demanded rent from residents.

The man said the fire began after he used fuel to set light to the body of a man he had strangled while high on drugs, in a ground floor room used to beat people targeted by the dealer.

Police arrested him at the inquiry. They say he is due in court on Thursday accused of arson, 77 murders and 120 attempted murders.

Johannesburg, known as the city of gold, is Africa's wealthiest city.

The fire has highlighted the profound housing crisis here.

Many people live in appalling conditions, without water or electricity, in deeply unsafe buildings.

Image source, Ed Habershon/ BBC

Image caption,Over 500 people were left homeless by the fire

The plight of the fire's survivors demonstrates the crisis still further.

More than 500 people were left homeless by the fire. The residents are some of the poorest people in South African society.

In the immediate aftermath, South African President Cyril Ramaphosa visited the scene and declared "our hearts go out to every person affected by this event".

He said the disaster called on everyone, from the government down, to help restore the wellbeing of those affected and "offer all material help residents may need".

But, five months on, many survivors are suffering.

We visited 39 families who have been placed by the authorities in a newly built camp of metal shacks, which have no water or power, and which flood when it rains.

Sthembiso Ndebele lives in one of the shacks with her three children, including her disabled 10-year-old son, who she said is not coping with the conditions.

She asked President Ramaphosa to "please give us housing not these shacks - these shacks are too dangerous for us".

Image source, Daniel De Simone/ BBC

Image caption,Sthembiso Ndebele was placed by authorities in a camp of metal shacks and has no water or power

Hundreds of people living in the shacks have access to only two communal taps, a few chemical toilets which residents say are deeply unhygienic, and no showers or bathing facilities.

We saw men cooking on open fires, with elderly women shovelling sand around the bottom of their shacks to stop water getting in.

The Denver area of the city where the shacks have been placed is dangerous, and one girl has been raped, the residents said.

At first, multiple security guards were provided to keep watch, but these were withdrawn, leaving a single guard on a daytime shift by the time we visited.

Andy Chinnah, a human rights activist who is helping the residents, said: "We want dignity and this is not dignity".

When I challenged Johannesburg's Mayor, Kabelo Gwamanda, on the camp's conditions, he said there was not "sufficient budget for us to be responding efficiently or in the manner in which we want to", especially when "unplanned" emergencies occur.

He said that, in the past, the city had decent alternative accommodation, but those properties "got hijacked".

This was a reference to the city's so-called "hijacked buildings".

Matthew Wilhelm-Solomon, author of The Blinded City, says the term emerged in the early 2000s and referred to criminal gangs taking over some properties.

He says it was subsequently applied by the media and politicians to an array of buildings, even though many did not have gangs taking over and illegally renting them.

Wilhelm-Solomon says that what was essentially a crisis about affordable inner city rental properties began to be viewed "through the lens of criminality", which ended up criminalising people who were just looking for accommodation.

Many buildings in the city have been abandoned or neglected by owners and left without basic services or safety measures.

The law gives people evicted from such buildings the right to emergency temporary accommodation. But the profound lack of affordable housing means this is rarely offered.

The camp of metal shacks is the authorities' current offer of such temporary accommodation, but those living there wonder how long "temporary" will turn out to be.

Image source, Chris Parkinson/ BBC

Image caption,Authorities say the shacks are temporary accomodation

An estimated 15,000 people are believed to be homeless in Johannesburg.

The mayor says there are now 188 "bad buildings" under investigation, with 134 of them in the inner city, and that the city authorities are pursuing multiple court cases to evict people, approaching them as places from which they need to be rescued.

Courtrooms are a battle ground in the struggle for decent housing.

After the Usindiso building fire, there were 248 people at the scene who agreed to be relocated to various shelters, according to court documents, with some foreign nationals refusing to be relocated to shelters due to fear of deportation.

Thirty-two foreign nationals were arrested and placed in a repatriation centre, but human rights groups went to the high court and obtained an order preventing the state from deporting them for now as they are witnesses in the ongoing public inquiry.

At one stage, the Department of Home Affairs claimed the main support groups for the fire's victims did not exist and that residents should have brought a court case in their individual names, but the court rejected the government's arguments.

In the meantime, the danger remains in Johannesburg's "bad buildings".

One property that has been a focus of attention is Vannin Court, long without water or power, and which is falling into deep disrepair.

The broken lift shaft is dangerously open, with children walking past in the darkness, and the fire escape lacks stairs as thieves have stolen them for scrap metal.

Some residents have been living in the property for decades and say they feel abandoned.

Vannin Court has been subjected to high-profile police raids, with politicians and media in tow, and five years ago the local authorities received publicity after claiming the property would be totally redeveloped - a pledge that was never followed through.

Image source, Daniel De Simone/ BBC

Image caption,Residents of Vannin Court say they feel abandoned

Mukelwa Mdunge, who lives in Vannin Court with her family, told us that facilities in the building once worked but had fallen into tragic dereliction, with the darkness and a lack of security creating constant danger for residents.

But she says the residents have no other option, and do not want to be evicted into even more uncertain conditions.

"This one is our home, where can we go?"

At the inquiry into the fire, where the confession came this week, damning evidence is now being heard about an entire culture of safety and security for the poorest in society.

Last week, fire safety expert Wynand Engelbrecht said the condition of the Usindiso building was not unlike that of hundreds other similar buildings in South Africa.

"It is clear both privately-owned and public sector-owned structures are far too often left to deteriorate to the point of no-return.

"Life safety is not a priority in this country, not even by a long shot."

The current reckoning is barely beginning, let alone near an end.

The suffering behind Johannesburg's neglected walls will not be contained.

11 months ago

101

11 months ago

101

English (US) ·

English (US) ·