ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, ASTROSCALE

Image source, ASTROSCALE

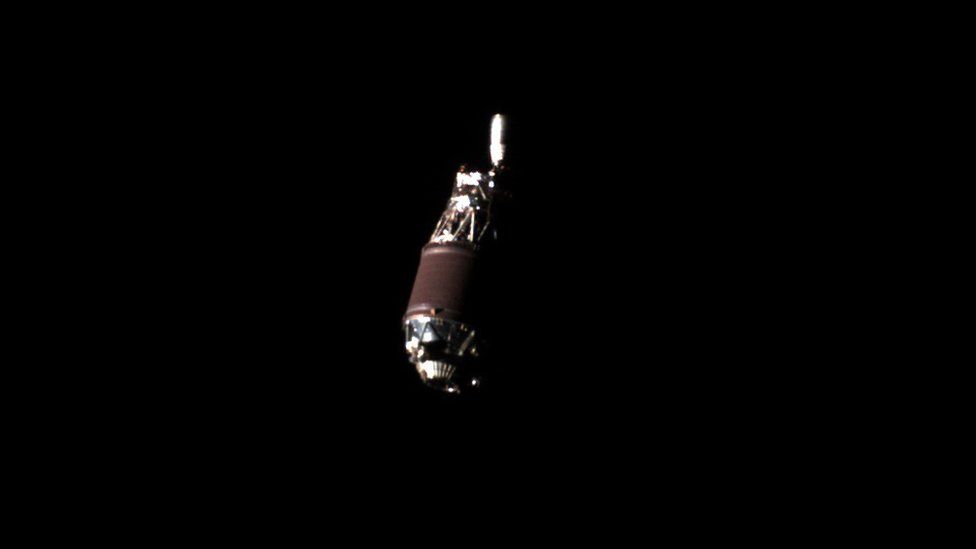

The old rocket segment comes into view about 600km above the Earth

A satellite operated by Japanese company Astroscale has chased down a 15 year-old piece of space junk and taken an up-close image of it.

The object is a discarded rocket segment that's about 11m by 4m (36ft by 15ft), with a mass of three tonnes.

It's the first time anyone has managed to rendezvous with so big a piece of space debris.

Astroscale is developing a business that would offer to remove others' redundant hardware from orbit.

It won't do it on this occasion; the current mission is all about testing the sensors and software needed for safe proximity operations. But a determined effort to pull a lump of junk out of the sky should occur in the next couple of years, the firm says.

The issue of orbital debris and the sustainable use of space is becoming a hot topic right now.

Millions of items of techno-detritus have accumulated overhead since the start of the space age in 1957 - from flecks of paint to the abandoned upper-stages of rockets, like the one just pictured by Astroscale.

Image source, Astroscale

Image caption,The inspection satellite Adras-J will spend the next weeks surveying the rocket segment

This wandering swarm of metal and other materials runs the risk of colliding with, and destroying, the functional satellites we use to communicate and monitor the planet.

Rocket bodies are a particular hazard because of their immense bulk.

The one in the new image came from Japan's H-IIA launch vehicle, which lofted a CO2-measuring spacecraft called Gosat, in 2009.

The upper-section of the rocket ejected Gosat at an altitude of roughly 600km.

But whereas more modern rockets make sure all their parts come back down to Earth soon after a flight, this H-IIA stage stayed up there. And it's far from being alone.

The European Space Agency has counted 2,220 rocket bodies still in orbit today.

Image source, ASTROSCALE

Image caption,Future missions will use robotic arms to reach out and grab space junk

Astroscale calls its rendezvous mission Adras-J, or Active Debris Removal by Astroscale-Japan.

It's being performed by a smart spacecraft that was launched on 18 February. The satellite has been closing in on the H-IIA body ever since.

Adras-J used cameras and algorithms to make the final approach. Great care is needed not to bump into the rocket segment, which is slowly turning end over end.

Astroscale's UK employees built the "ground segment" for the mission, which is the system used to communicate with Adras-J. They've also done much of the "flight dynamics" work, which is all about precise navigation.

Around-the-clock operations have been shared by Mission Control in Tokyo and the company's British base at Harwell in Oxfordshire.

The plan is to spend the coming weeks taking more imagery and gathering information on the rocket segment, such as the condition of the structure, its spin rate, and spin axis.

Adras-J will will attempt to fly around the rocket body in the process.

Future Astroscale missions will move in and grab hold of their quarry with the aid of robotic arms.

Image source, Astroscale

Image caption,Artwork: How the scene might appear from the rocket's perspective, looking back at Adras-J

On this occasion, Adras-J will limit itself to an experiment in which it will try to slow the tumbling rate of the rocket stage.

The activity will involve firing thrusters at the body in a direction opposite to its spin motion. The pressure of the thrusters' plume ought to decelerate the rotation rate.

A number of companies around the world are developing technologies similar to Astroscale.

Experts say that to prevent a cascade of collisions in orbit, it's imperative space-faring nations start removing several large pieces of junk every year.

1 year ago

101

1 year ago

101

English (US) ·

English (US) ·