ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Jehad El-Mashhrawi

Image source, Jehad El-Mashhrawi

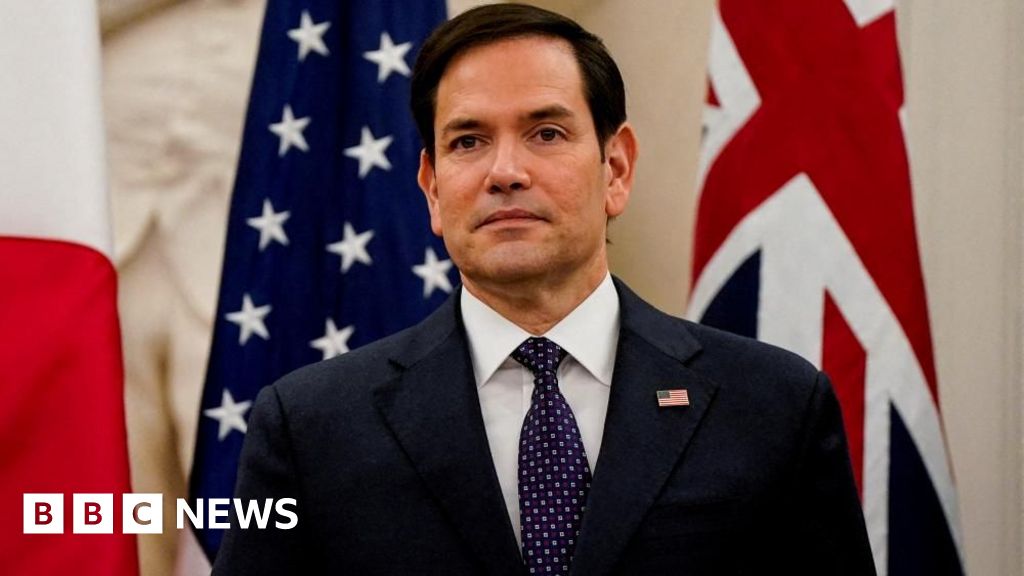

Jehad, his wife and their four sons at home before the war

After weeks of Israeli bombing, on 16 November Jehad El-Mashhrawi and his young family fled their home in northern Gaza. The BBC Arabic cameraman shares a vivid and shocking account of what he, his wife and children experienced as they headed south.

Warning: This story contains graphic descriptions which may be distressing

We left in such a hurry. We were in the middle of baking some bread and realised the houses opposite us were being bombed, one by one. I knew it would soon be our turn. We had packed some bags in case this happened but everything was so rushed we forgot to take them. We didn't even shut the front door.

We had waited to leave because we didn't want to move my elderly parents and we had taken years to save up to build our house in al-Zeitoun, but in the end we had to go. My baby son, Omar, died there in November 2012, killed when shrapnel hit our house in another war with Israel and I couldn't risk losing any more children.

I knew that in the south there was no electricity, no water and people had to queue for hours to use a toilet. But in the end, grabbing just a bottle of water and some leftover bread, we joined thousands of others making the dangerous journey down the Salah al-Din road to the south, where Israel said it was safe.

Image source, Majed Hamdan/Associated Press

Image caption,Jehad's son Omar was 11 months old when he was killed in 2012

Lots of my family walked together - my wife Ahlam, our four sons, who are two, eight, nine and 14 years old, my parents, brothers, sisters, cousins and their children.

The Salah al-Din road

We walked for hours and knew that eventually we would have to go through an Israeli checkpoint that was set up during the war. We were nervous and my children kept asking: "What will the army do to us?"

We came to a stop about two-thirds of a mile (1km) from the checkpoint and joined a huge queue of people that filled the entire road. We spent more than four hours waiting there and my father fainted three times.

There were Israeli soldiers watching us from bombed-out buildings on one side of the road and more on an empty plot of land on the other side.

As we edged closer to the checkpoint we saw more soldiers above us in a tent on a hill. We think they managed the checkpoint remotely from there, watching us through binoculars and using loudspeakers to tell us what to do.

There were two open-sided shipping containers near the tent. All the men had to pass through one and the women through the other, with cameras constantly trained on us. When we had gone through, Israeli soldiers asked to see our IDs and we were photographed.

It was like judgement day.

Image source, Maxar

Image caption,This satellite photo shows a large crowd of people waiting to pass through the checkpoint on 17 November 2023

I saw about 50 people detained, all men, including two of my neighbours. One young man was stopped because he had lost his documents and couldn't remember his ID number. Another man next to me in the queue was called a terrorist by an Israeli soldier, before he too was taken away.

They were told to strip down to their underwear and sit on the ground. Some were later asked to get dressed and leave, while others were blindfolded.

I saw four blindfolded detainees, including my neighbours, taken behind a sand hill by a demolished building. When they were out of sight, we heard gunfire. I have no idea whether they were shot or not.

Separately, other people who made the same journey as me were contacted by a colleague of mine in Cairo. One of them, Kamal Aljojo, said that just after he went through the checkpoint a week earlier, he had seen dead bodies, but he didn't know how they had died.

My colleague also spoke to a man called Muhammed who went through the same checkpoint on 13 November. "A soldier asked me to strip off all of my clothes, even my underwear," Muhammed told the BBC. He added: "I was naked in front of everyone walking past. I felt ashamed. Suddenly a female soldier pointed her gun at me and laughed before quickly moving it away. I was humiliated." Muhammed said he had to wait naked for about two hours before he was allowed to go.

Although my wife, children, parents and I all got through the checkpoint safely, two of my brothers were delayed.

While we were waiting for them, an Israeli soldier shouted at a group of people in front of us who were trying to go back towards the containers to check on their relatives, who had been held up.

He used a loudspeaker to tell them to move on and to stay at least 300yds (300m) away, then a soldier started shooting in the air in their direction to intimidate them. We had heard a lot of gunshots while we were queueing.

Everyone was crying and my mother was sobbing: "What happened to my sons? Did they shoot them?"

After well over an hour my brothers finally appeared.

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF) told the BBC that "individuals suspected of affiliations with terrorist organisations" were detained for preliminary inquiries, and if they remained suspects they were transferred to Israel for further questioning. Others were "promptly released", it said.

It said clothes had to be removed to check for explosive vests or other weapons and detainees were clothed as soon possible. It said it did not aim to "undermine the security and dignity of the detainees" and that the IDF "operates in accordance with international law".

The IDF also said it "does not shoot at civilians moving along the humanitarian corridor from the north to the south", but when young men tried to move in the opposite direction they "were met with shots for the purposes of dispersal, after they were told with a loudspeaker not to advance towards the position of the troops and continued to do so".

It added that the sound of shooting was common and "the sound of gunfire alone does not constitute an indication of shooting from a specific place or of a certain type".

My wife and I felt relieved as we moved on and the checkpoint disappeared from sight behind us, but we had no idea that the hardest part of the journey was yet to come.

As we walked further south, I saw about 10 bodies in different places by the roadside.

Other scattered, rotting body parts, were covered in flies with birds pecking at the remains. They gave off one of the foulest smells I have ever experienced.

I couldn't bear the thought of my children seeing them so I screamed at the top of my lungs, telling them to look at the sky and keep walking.

I saw a burned-out car with a severed human head inside. The hands of the headless rotting corpse were still holding the steering wheel.

There were also bodies of dead donkeys and horses, some reduced to skeletons, and huge piles of rubbish and spoiled food.

Then an Israeli tank appeared on a side road, moving towards us at breakneck speed. We were frightened and in order to get away, we had to run over corpses. Some people in the crowd tripped on the bodies. The tank changed course about 20yds (20m) before it reached the main road.

Suddenly, next to the road, a building was bombed. The explosion was terrifying and shrapnel flew everywhere.

I wanted the world to swallow us up.

We were shaken and exhausted but carried on towards Nuseirat camp. We arrived there in the evening and had to sleep on the pavement. It was freezing.

We put my jacket around our middle sons, tucking their hands into the sleeves to try to keep them warm. We covered our youngest with my shirt. I have never been so cold in all my life.

When the BBC asked about the tank and the bodies, the IDF said that "during the day, tanks move on routes that intersect with the Salah al-Din road, but there was no case in which tanks moved towards civilians moving from north to south of the Gaza Strip on the humanitarian corridor".

The IDF said it did not know of any cases of piles of corpses on the Salah al-Din road but there were times when Gazan vehicles "abandoned bodies during the journey, which the IDF subsequently evacuated".

The search for safety

The next morning we set off early for Khan Younis, Gaza's second largest city. We paid someone to take us part of the way in a cart pulled by a donkey. Then at Deir al-Balah, we got on a bus that was only meant to carry 20 people, but 30 people got on board. Some sat on the roof and others clung to the doors and windows from the outside.

In Khan Younis, we tried to find a safe place to stay at a UN-run school that had been turned into a shelter, but it was full. We ended up renting a warehouse under a residential building instead and stayed there for a week.

Image source, Jehad El-Mashhrawi

Image caption,Jehad cooks over an open fire for his family in Rafah

My parents, brother and sisters decided to stay in Khan Younis, but after the local market was bombed, my wife and I decided to take our children further south to Rafah to be with her family. They managed to get a lift in a car and I joined them later by bus, but it was so full I had to hang on to the outside of the door.

We are now renting a small outhouse with a roof made of tin and plastic. There is nothing to protect us from falling shrapnel.

Everything is expensive and we can't get many of the things we need. If we want drinking water, we have to queue for three hours and we don't have enough food for three meals a day, so we don't eat lunch any more, only breakfast and dinner.

My son used to have an egg every day. An egg - can you imagine? I can't even give him that now. All I want to do is leave Gaza and be safe with my children, even if that means living in a tent.

Additional reporting by BBC News Arabic's Abdelrahman Abutaleb in Cairo.

1 year ago

24

1 year ago

24

English (US) ·

English (US) ·