ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, EPA

Image source, EPA

Dropping aid into Gaza from the sky is fast becoming a last resort way to get food to starving people

By Lucy Williamson

BBC News, above the Gaza Strip

One thousand miles east of Gaza, large blocks of aid are being loaded on to a US military transport plane, its crew silhouetted by the morning sun glancing over the desert landscape around Qatar's al-Udeid airbase.

They push 80 crates into the plane's cavernous interior, each canvas-wrapped block strapped to a cardboard pallet and topped with a parachute.

Feeding Gaza is now a complex, risky, multi-national operation. The RAF carried out its first two aid flights this week. France, Germany, Jordan, Egypt and the UAE have also been taking part.

This was the 18th mission flown by US forces. Dropping 40,000 ready-prepared meals into the tiny, besieged war-zone requires them to make a six-hour round trip from Doha.

It is more expensive and less efficient than other ways of delivering aid and it is also harder to control.

Earlier this week, 12 people are thought to have drowned while trying to retrieve aid parcels that fell into the sea. Another six were reportedly crushed in the stampede to reach it.

"We're very aware of all the news, and we're trying to limit casualties," said Maj Boone, the mission commander, standing beneath a large American flag at the entrance to the cockpit.

"[We're doing] literally everything we can. We use a chute that falls at a slower rate to give Gazans more time to see the parachute and get out of the way.

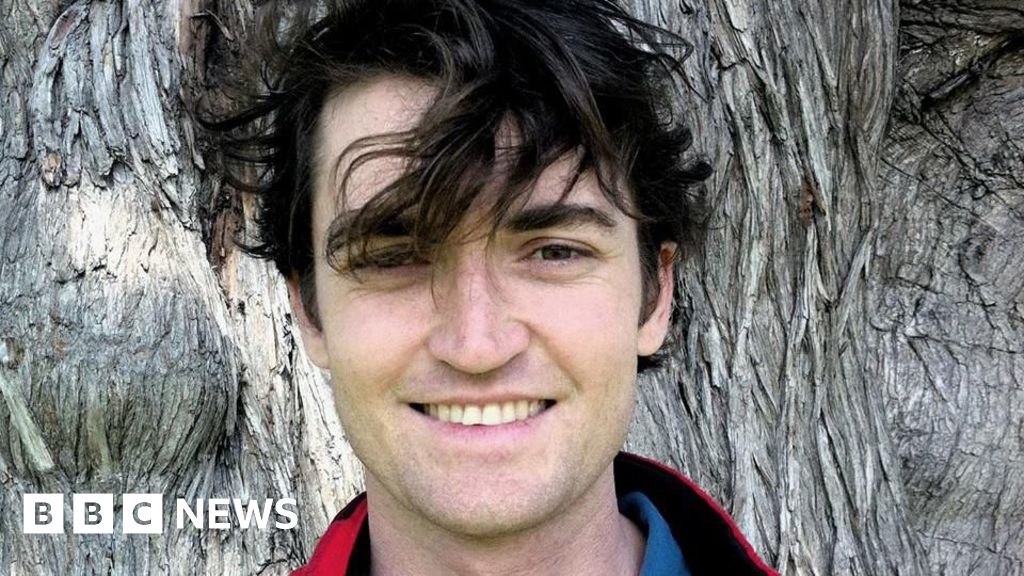

BBC News went onboard an aid flight to see a US drop taking place over Gaza

"We also have assets overhead that clear the drop zone, so we won't drop if there's any group of people there."

He said they mapped the route carefully, aiming to land the aid in safer, open spaces along the Gaza coast, but drop the parcels over the sea so that crates with malfunctioning parachutes would drop into the water, rather than on buildings or people.

A heavy military cargo plane can be heard for miles around, meaning crowds quickly gather to follow it.

Desperation leads many to take enormous risks to retrieve the aid - and many come away with nothing.

Hamas has reportedly demanded a halt to air drops as casualties have grown, calling them "useless" and a "real danger to the lives of hungry civilians".

The risks are increased by the lack of any organised distribution of the aid once it hits the ground.

As we swing down low over Gaza, the plane ramp opens to reveal the outskirts of the Strip's devastated capital city - its remaining tower blocks jutting up like lone naked teeth.

American food parcels are being targeted at places where American-made weapons have already made their mark.

The roads beneath us along the coast were busy with people and vehicles, moving quickly in the same direction, apparently racing the plane.

Image source, Reuters

Image caption,The US military has issued images of the planes it uses to transport the aid packages

We watched as the parachutes slipped quickly out, shrinking to specks in seconds. Many hung over the water - but two, their parachutes stalled, crashed straight into the sea.

"It's not perfect," said US Airforce spokesman Sgt Robert Porter when asked whether aid drops were the best approach to Gaza's hunger crisis.

"We know there's upwards of two million people who need food on the ground - innocent civilians who did not ask for this conflict - and we're dropping meals in the tens of thousands.

"Does it feel like a drop in the bucket? Maybe a little bit - but if you're a family on the ground who got some of this aid, it can be a lifesaver."

On the ground in Gaza, a journalist working with the BBC watched the US parachutes fall. He counted 11 air drops that day. Some residents in northern areas reportedly spend their days watching the skies for aid planes.

"We have tried twice this morning, but in vain," said another Gaza City resident, Ahmed Tafesh. "If we can at least get a can of beans or hummus to support ourselves, we hope we will eat today. Hunger has consumed most people, they have no energy anymore."

A recent global assessment warned of imminent famine in Gaza, prompting the UN's top court this week to order Israel to enable an immediate "unhindered" flow of aid.

"If people are starving and we're giving them food, that's the best we can do right now," said Maj Boone.

"I know other people are trying [approaches] that take more time. My team of C17s were notified and out here within 36 hours and doing everything in our potential to get food to people who need it."

Watch: Gazans reportedly drown after video shows rush for aid drop that landed in sea

Israel has rejected both the famine assessment and the UN court order, saying allegations that it is blocking aid are "wholly unfounded". It has accused Hamas of stealing aid.

But humanitarian aid for Gaza is one of the issues dividing the US and Israel over this war at the moment.

The US is building a temporary pier in Gaza to get more aid in quickly. Israel's busiest cargo port, 48km (30 miles) from Gaza City, has not been opened for aid.

US President Joe Biden has been pressing Israel's prime minister hard to expand access for land convoys - still the best way of getting large amounts of aid in quickly.

Scenes of sick, malnourished children dying in Gazan hospitals are shifting electoral politics in America, but he has so far been unwilling to use US arms supplies as leverage to drive his demand home.

Aid flights are multiplying among Arab and western nations. Risky and inefficient, they drop small amounts of food into a desperate population.

They are an eye-catching last resort.

Their value is measured in two simple questions: how much do they ease the pressure on Gaza's population and how much do they ease the pressure on governments elsewhere?

9 months ago

107

9 months ago

107

English (US) ·

English (US) ·