ARTICLE AD BOX

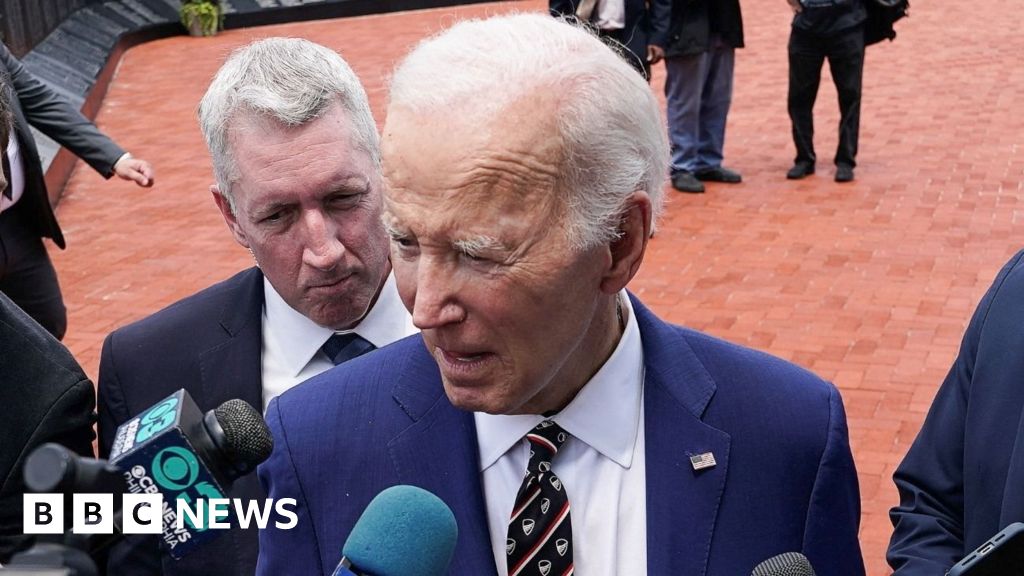

Andrea Díaz Cardona

BBC News Mundo

Submitted photo

Submitted photo

Aracely with her two daughters waited at a migrant shelter in Buffalo, New York while their case was being reviewed by a Canadian court

The Rainbow Bridge, which crosses the Niagara River between the United States and Canada, has for decades been a symbol of peace connecting two countries.

But for Araceli, a Salvadorian migrant, and her family, the bridge represented a seemingly insurmountable hurdle.

Along with her partner and two daughters, aged four and 14, the family first attempted to cross the bridge on 17 March.

They had arrived with a suitcase and documents that they believed assured them they would soon be reunited with Araceli's siblings on Canadian soil and escape the threat of US President Donald Trump's mass deportations.

But the plan failed. Not just once, but twice.

While a third attempt proved successful, immigration experts and official statistics point to a rise of asylum seekers at the border fleeing not just their homelands, but President Trump's immigration policies.

The exception to the rule

Araceli and her family had been living illegally in the US for more than a decade – only her youngest daughter, who was born in New Jersey, has a US passport.

In the US, Araceli built a life for herself and tried to initiate an asylum application process, but was unsuccessful.

"They charged me money and told me I would get a work permit. I paid that to a lawyer, but they never gave me an answer as to whether it was approved or not," she told BBC Mundo from a migrant shelter near the US-Canada border.

Araceli has 12 siblings, and like her, several left El Salvador due to safety concerns in the rural community where they grew up. Two of them managed to start from scratch in Canada.

After President Trump's inauguration, amid reports of mass raids and deportations, Araceli began to fear for her and her family's safety – especially after the administration began sending illegal migrants to a notorious Salvadorian prison.

But because both Canada and the US have signed onto the "safe third country agreement," migrants, like Araceli, who have been denied refuge in one country are not supposed to be granted asylum in the other. The agreement states that asylum seekers must apply for asylum in the first country where they land.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The Rainbow Bridge connects the US to Canada

There are exceptions. One of them is if the asylum seeker arriving from the US can prove they have a close relative in Canada who meets certain requirements, they can enter the country and begin their refugee claim again.

So Araceli and her family said goodbye to the life they had built in the US to join her two brothers in Canada.

After crossing the Rainbow Bridge, they arrived at the border check point to make their asylum claim. She said she had all the original documents proving her relationship to her brother.

"They took everything, even our backpack, and we were left with nothing,"

They spent the entire night in a waiting room, occasionally answering questions, until an agent found a problem with the application.

"They found a small detail: on my [birth] certificate, my father only had one last name, and on my brother's, he had two."

And although the document had a clarification explaining that such inaccuracies are common in El Salvador, the agent denied them entry to Canada.

Getty Images

Getty Images

The Rainbow Bridge is one of the few places you can easily walk through customs

A second attempt

The family returned, resigned and anguished, having to face their greatest fear: being separated and deported.

At the US checkpoint, they were put in a room with no windows.

"The four of us spent 14 days in that cell," Araceli said, clarifying that they could go out to use the bathroom, but were barely allowed outside.

Her brother reached out to an organisation that works with migrants, who helped them hire an attorney, Heather Neufeld.

While she was preparing their documentation, and without any explanation, the family was given an apparent second chance.

"Two agents arrived at the cell and said: 'Congratulations, you're going to Canada'," Araceli recalled.

But their hopes were short-lived.

"We've been too generous in welcoming you back here," she recalled the agent saying after the family applied for asylum in Canada a second time. "The United States will see what it does with you."

A spokesperson declined to comment on Araceli's case in particular, citing the country's privacy laws.

One thing is for sure - more families like Araceli's are seeking exceptions to come to Canada.

While the number of people attempting to cross into the United States from Canada has decreased significantly, the number of asylum seekers being denied entry into Canada from the US has increased.

According to official figures from the United States government,13,547 apprehensions were reported along the entire northern border as of March 2025 – a 70% decrease compared to the number recorded in the first quarter of 2024.

Conversely, the number of migrants seeking asylum in Canada and being returned to the US has increased this year, according to data from Canada Border Services Agency (CBSA).

In April of this year, 359 people, including adults and children, were found ineligible for asylum in Canada, compared to 180 people in April 2024.

Ms Neufeld believes the increase in the number of people turned away is due to "stricter" border policy at the Canadian side. In December 2024, Canada announced an investment of C$1.3bn ($950m; £705m) to "strengthen border security and strengthen the immigration system".

The move was largely seen as an attempt to placate Trump, who has justified widespread tariffs against Canada by blaming the country for illegal immigration into the US.

In February, amid a brewing trade war, the Canadian government announced it would further expand this programme.

The CBSA has also committed to increasing the number of removals from 16,000 to 20,000 (a 25% increase) for fiscal years 2025-2027.

Still, a spokesperson for CBSA told BBC Mundo that they have not changed how they do things: "We have made no changes to policies or processes".

Submitted photo

Submitted photo

Aracely with her two daughters at a migrant shelter in Buffalo, NY

Immigration Confusion

Denied entry to Canada for the second time, Araceli and her family had to cross the border back into the US, which scared them.

"In this day and age, it's not just about being sent to the United States. There's an immediate risk of detention and deportation," Ms Neufeld said.

The problem now was that this second trip to Canada was counted as a reconsideration of the case, the only one the family is entitled to under that country's regulations.

Ms Neufeld said that Canadian border agents made a mistake.

"They didn't act like they had in the past with other clients, nor did they agree to an interview with the brother when they normally do," she stated.

According to Ms Neufeld, the family didn't return to Canada of their own free will, but because the US authorities told them to, and so their second attempt should not have been considered an official reconsideration.

To get a third opportunity to cross the border and make an asylum claim, Araceli would need a Canadian court to intervene.

When they returned to America, her partner was sent to an Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) detention centre, while Araceli was made to wear an ankle monitor and she and her children went to a migrant shelter.

"They came to tell us they were giving us three minutes to say goodbye because my husband was going to be taken to a detention center," Araceli recalls, her voice breaking.

Many more like this

A week later, following complex negotiations between the lawyers, a Canadian federal court agreed to allow the family to return to the border to be re-evaluated.

On 5 May, seven weeks after the first attempt, Araceli crossed the bridge once again. This time, she had her lawyer with her.

After 12 hours, a border agent opened the doors and said "welcome to Canada and good luck with your new life", she recalled.

"I felt immense joy, it's indescribable," Araceli told Canadian public broadcaster CBC earlier in May, adding: "My daughters gave me so much strength."

But it was a bittersweet celebration, as her partner remained in the US for two more weeks, caught up in ongoing legal proceedings. The family hired a lawyer to take on his case.

"They managed to get him out on bail, and that's something not all detention centres allow. The whole family had to make a huge effort; they had to sell things to be able to pay for it," Ms Neufeld said.

According to her, this family's case reflects the changes that have recently occurred on the northern border.

"There are many more Aracelis, but we can't know where they are or what situation they are facing. Most people lack the capacity to fight to have their rights respected."

1 day ago

6

1 day ago

6

English (US) ·

English (US) ·