ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Getty Images

Image source, Getty Images

Unblurred images of Muhammad Hani al-Zahar, a baby with rigor mortis, were used online to claim his death was faked

By Olga Robinson & Shayan Sardarizadeh

BBC Verify

The mother and grandfather of five-month-old Palestinian baby Muhammad Hani al-Zahar held his dead body in front of a hospital following the resumption of hostilities in Gaza on the first day of December.

But when footage of the grief-stricken family holding the body in their arms went viral on social media, many posts falsely claimed Muhammad was merely a doll, and not a real baby.

These claims were amplified in an article by the Jerusalem Post, an influential Israeli newspaper, which showed an image of Muhammad in rigor mortis after his death and said it proved he was a doll. After a backlash, the paper removed the article from its website, saying on X (formerly Twitter) that the report "was based on faulty sourcing".

A few weeks earlier, a video of Israeli siblings Rotem Mathias, 16, and his two sisters, Shakked and Shir, went viral online. Rotem witnessed his parents get killed by Hamas gunmen on 7 October as they sheltered in their house in a kibbutz near the border with Gaza.

The viral video featured edited clips from the siblings' interviews with US outlets ABC and CNN days after the attack. It falsely claimed that they were "crisis actors" who were lying about their parents' deaths and struggling to hold their laughter in front of cameras.

Image source, ABC News

Image caption,Rotem Mathias, centre right, was falsely accused of being a "crisis actor" after ABC News spoke to him about the killing of his parents

These are just two examples - viewed millions of times each - showcasing the social media schism in the Israel-Gaza war that has brought denial of atrocities and human suffering to the forefront of online debate about the conflict.

One of the key terms used to deny or minimise human suffering in Gaza is "Pallywood", a disparaging combination of "Palestine" and "Hollywood". Its proponents claim fake or staged footage of Palestinian "crisis actors" posing as genuine civilian casualties is regularly shared online to influence public opinion and deceive global media.

A BBC Verify analysis suggests that on X alone, the term "Pallywood" has seen the largest spike in the number of mentions in the past 10 years.

During previous flare-ups of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict in 2014, 2018 and 2021 the word "Pallywood" consistently peaked at either 9,500 or 13,000 mentions in a single month on X. After the 7 October Hamas attack, the number of mentions peaked at 220,000 in November.

BBC Verify found that among those sharing the term "Pallywood" on social media in the past months, including X, Facebook and Instagram, were Israeli officials, celebrities and popular bloggers from Israel and the US.

On the other hand, while supporters of the Palestinians do not have a single term used to deny atrocities committed by Hamas on 7 October in Israel, posts making such claims routinely get millions of views on social media. Some falsely say that Hamas did not kill civilians on that day, or that the scale of civilian casualties has been massively exaggerated. Some even go further, falsely claiming that most of the victims were actually killed by the Israel Defense Forces, not Hamas.

Experts specialising in reconciliation efforts worry that viral disinformation which denies the other side's suffering can be dehumanising, and may impact the longer-term prospects of mending the relations between the communities affected.

"The biggest risks, I think, are the erosion of trust and the erosion of empathy," said Harriet Vickers, programme lead at the Tim Parry and Johnathan Ball Foundation for Peace, a charity that supports victims of conflict, political violence and acts of terror.

"It undermines the ability to even begin approaching reconciliation efforts."

She added that false narratives and dehumanising rhetoric can also "have a profound effect beyond those that are directly impacted by violence, and can actually further the hurt that is being done to those individuals".

False narratives about "crisis actors" or atrocity denial are not new to those who study disinformation.

The concept of "crisis actors" in particular - that is people who pretend or are paid to act out some particular tragedy or disaster - has been popular among promoters of conspiracy theories for years.

It was notoriously used to allege that parents of dead children in the Sandy Hook school shooting in the US were somehow faking their personal tragedies.

In the past few years similar viral claims were posted about the killing of Ukrainian civilians in Bucha, and victims of the war in Syria.

But the volume of dehumanising rhetoric posted during this war has surprised even those who deal with such content on a daily basis.

Eliot Higgins, the founder of the investigative website Bellingcat that has covered the wars in Syria and Ukraine in recent years, says the volume of disinformation in the current Israeli-Gaza war is "unique to this conflict".

"I've seen the kind of same intensity of toxicity and vile responses and disinformation, the way they treat women and children and that kind of stuff, with Syria, with Ukraine and so many different topics - just there are more people doing it," he told the BBC.

Image source, Mahmoud Ramzi

Image caption,Images of a child actor in behind-the-scenes footage of a Lebanese video were used to discredit claims of Palestinian suffering

Mr Higgins added that because many people have had very strong opinions about either side of the conflict for years, "there are more people who are sharing stuff because it is resonating with them emotionally".

"They don't really care if it's true or not, it just feels true to them."

Back in November, a video showing makeup and fake blood being applied to a child actor's face was posted on X by Ofir Gendelman, the Israeli prime minister's spokesperson to the Arab world.

"See for yourselves how they fake injuries and evacuating 'injured' civilians, all in front of the cameras. Pallywood gets busted again," Mr Gendelman said in a post that was viewed millions of times before being deleted.

The video was, in fact, behind-the-scenes footage from a 45-second Lebanese film made in tribute to Gazans and posted online in October.

Director Mahmoud Ramzi, who took to Instagram to personally debunk the false claim made about his film, told the BBC that in the end, the misinformation might have backfired, with the controversy helping his film reach a much bigger audience.

The BBC approached Mr Gendelman for comment but he has not responded.

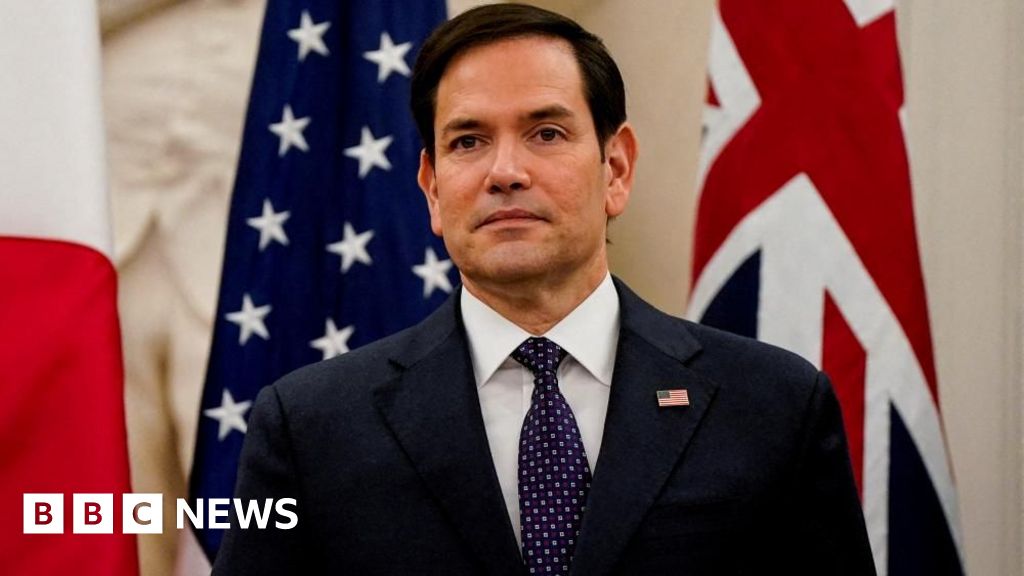

Image source, Getty Images

Image caption,Israeli spokesman Ofir Gendelman initially shared footage of a Lebanese film claiming it showed Palestinian injuries were faked

Others have expressed concern for the real people who find themselves in the middle of online disinformation wars. James Longman, the ABC correspondent who interviewed Rotem and his sisters, says watching Rotem recount the death of his parents brought him and his cameraman to tears.

"He was in tears, his sister was in tears, their grandfather, who was with us. Our cameraman, the hospital porters, the nurses, the doctors, and I was in tears. I mean all of us sitting there listening to what he had to say," he told the BBC.

"It was extraordinary to hear him say it, to watch his reactions as he explained what had happened."

Mr Longman said he was shocked when he saw false claims about the siblings being shared online and took to X to debunk it. His post was shared widely, and led to at least one of the viral messages about the siblings being subsequently deleted by the person who posted it.

"But it doesn't make it any less horrible for Rotem's family," Mr Longman said.

1 year ago

19

1 year ago

19

English (US) ·

English (US) ·