ARTICLE AD BOX

Image source, Reuters

Image source, Reuters

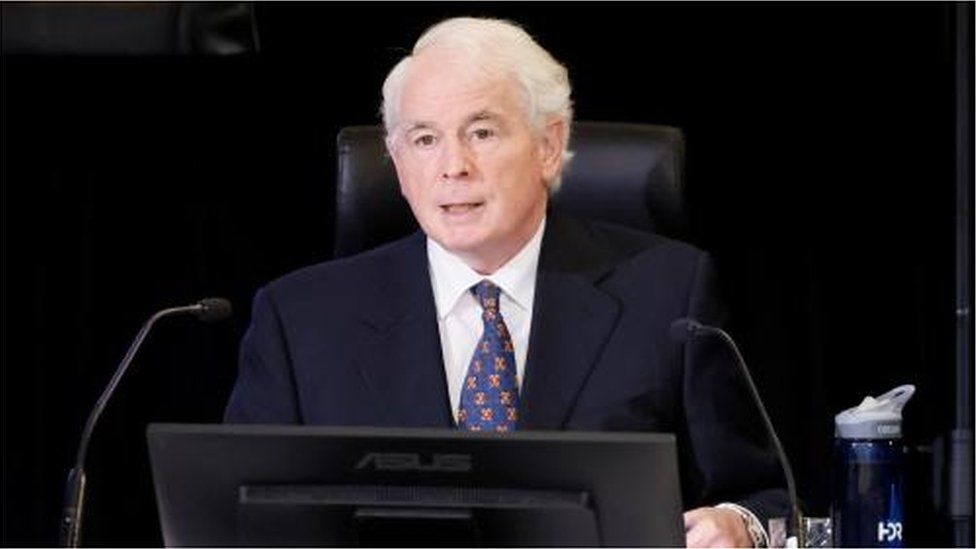

Justice Paul Rouleau said he expected the hearings could sometimes be "adversarial"

By Jessica Murphy

BBC News, Toronto

An inquiry into the first-ever use of government emergency powers to bring an end to the "Freedom Convoy" protest that gridlocked Canada's national capital last winter completes its public work this week, with Prime Minister Justin Trudeau expected as its final witness.

The Public Order Emergency Commission is examining whether the Trudeau government was justified in invoking the Emergencies Act to bring an end to the anti-vaccine mandate and anti-government protests that gridlocked the country's national capital and blocked vital border crossings, costing the economy millions of dollars a day.

Over six weeks, the inquiry has offered a rare glimpse behind the curtain into how Canadian officials handled the unprecedented protests that drew the global attention - and revealed plenty of frustration, "intemperate" text messages, and finger-pointing as they sought to bring an end to the blockades.

A final report on the inquiry's findings will be released early next year.

'You don't have to blow everything up to render it unusable'

In the lead up to Mr Trudeau's testimony, the inquiry, headed by Justice Paul Rouleau, is hearing from a series of federal ministers, including Bill Blair, who holds the Emergency Preparedness portfolio.

Mr Trudeau has said that invoking the Act - which allowed the government to temporarily impose bans on public assembly in some areas, prohibit travel to protest zones, and gave authorities the ability to freeze bank accounts - was a necessary "last resort".

Mr Blair echoed that sentiment, saying his colleagues were reluctant to invoke the 1988 Act, but that stressed police resources and an "escalation" of protests - including further "threatened" blockades at the border - convinced him otherwise.

He said the blocking of critical infrastructure raised it to "an actual emergency".

"You don't have to blow everything up to render it unusable," he said.

The Ottawa protest lasted three weeks from late January to mid-February, but shorter-lived protests cropped up at two key border crossings, near Coutts, Alberta, and at the Ambassador Bridge, a vital trade route between the US and Canada.

Police cleared both those protests before Mr Trudeau invoked the emergency order.

But the inquiry heard that Washington expressed concerns about Canada's ability to keep supply chains open if they couldn't manage the protests.

Two provinces - Saskatchewan and Alberta - said they were caught unawares by the invocation of the Act, and one Alberta official felt Ottawa failed to offer timely help.

In February, Alberta had asked about the possibility of military help to remove vehicles at Coutts, but a text message from provincial Municipal Affairs Minister Ric McIver to Mr Blair - "Any update?" - to follow up on the request went unanswered for 11 days. By then, police had ended the blockade.

'It was a power struggle back and forth over control'

Convoy protesters at the inquiry painted a very different picture of those three weeks in Ottawa compared to city residents who testified about being harassed by convoy participants, feeling like hostages within their own homes, and of diesel fumes and deafening noise.

Image source, Reuters

Image caption,Convoy organisers testified earlier in the inquiry

Protesters, in comparison, described a "festive" gathering where people - even families - could come together to make themselves heard by the government after two years of Covid restrictions.

Still, there were tensions. Convoy organisers described infighting among various factions.

One organiser, Chris Barber, told the inquiry there was conflict over the role of Pat King, an activist known to have shared extreme views. Both men face criminal charges related to the protests.

Text exchanges showed some convoy leaders were wary of Mr King's history of inflammatory comments, including ones threatening Mr Trudeau, but they saw benefit in his large online following.

Mr Barber said it was "evident" there was tension between himself and Mr King.

"It was a power struggle back and forth over control," Mr Barber said.

There were also concerns over an anti-vaccine mandate "memorandum" shared by another group within the convoy that proposed overthrowing the government.

One of their lawyers representing the protesters also suggested convoy leaders received regular leaks from law enforcement "sympathetic" to their cause.

The convoy raised C$24m ($18m; £15m) from supporters, primarily in Canada and the US, the inquiry heard. Some funds were returned to donors while some remain frozen because of an ongoing lawsuit launched by Ottawa residents.

At the heart of the inquiry is whether the high legal bar to invoke the Act - specifically an "urgent and critical situation" that "seriously endangers the lives, health or safety of Canadians" - was met.

Among other measures, invoking the Act allowed the government to bring in tow trucks to remove the big rigs blocking Ottawa's city centre and to freeze an estimated 280 bank accounts linked to protesters.

Civil liberty groups and the convoy organisers have argued the use of the Act was an overreach.

A document from the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) warned that using the Act could "further the radicalisation of some towards violence" and "galvanise anti-government sentiment".

The intelligence service also had doubts that the protests met the defined national security threat threshold - but ultimately, CSIS director David Vigneault testified he recommended its use.

Mr Vigneault said a combination of factors - the unpredictability of the event, its variable size and scope, the strain on police resources and the fact that "there were ideologically motivated violent individuals who were interested" in the protests - led him "to believe that the regular tools were just not enough to address the situation".

'I'll be up their ass with a wire brush'

Tensions between various levels of government and different police forces came up frequently over the past six weeks.

According to a summary of an 8 February phone call between Mr Trudeau and Ottawa Mayor Jim Watson, the prime minister accused Ontario Premier Doug Ford of "hiding from his responsibility on it for political reasons".

Image source, Reuters

Image caption,Premier Doug Ford and Prime Minister Trudeau had some tense exchanges during the protests

Mr Watson then complained that Mr Ford had been skipping meetings of federal and municipal officials.

Mr Ford expressed his own frustrations to Mr Trudeau in a phone call the next day, accusing Ottawa's police and mayor of having "totally mismanaged" the situation.

Protesters at the time were blocking the Ambassador Bridge, halting trade between Detroit and Windsor, which alarmed the White House.

Mr Ford told Mr Trudeau he couldn't direct the provincial police to act, but vowed the force would have a plan in place.

"I'll be up their ass with a wire brush," he told the prime minister.

The premier of Canada's most populous province has publicly supported the Trudeau government's decision to invoke the emergency powers, but refused to testify at the inquiry.

2 years ago

36

2 years ago

36

English (US) ·

English (US) ·