ARTICLE AD BOX

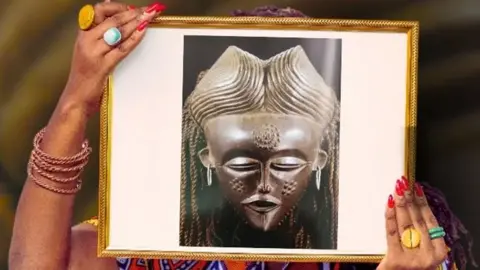

Women’s History Museum Zambia

Women’s History Museum Zambia

This sacred mask is etched with symbols of Sona, a sophisticated and now rarely used writing system

A wooden hunters' toolbox inscribed with an ancient writing system from Zambia has been making waves on social media.

"We've grown up being told that Africans didn't know how to read and write," says Samba Yonga, one of the founders of the virtual Women's History Museum of Zambia.

"But we had our own way of writing and transmitting knowledge that has been completely side-lined and overlooked," she tells the BBC.

It was one of the artefacts that launched an online campaign to highlight women's roles in pre-colonial communities - and revive cultural heritages almost erased by colonialism.

Another intriguing object is an intricately decorated leather cloak not seen in Zambia for more than 100 years.

"The artefacts signify a history that matters - and a history that is largely unknown," says Yonga.

"Our relationship with our cultural heritage has been disrupted and obscured by the colonial experience.

"It's also shocking just how much the role of women has been deliberately removed."

Women’s History Museum Zambia

Women’s History Museum Zambia

Samba Yonga holding the wooden hunters' toolbox in one of the beautifully photographed images posted on social media for the Frame project

But, says Yonga, "there's a resurgence, a need and a hunger to connect with our cultural heritage - and reclaim who we are, whether through fashion, music or academic studies".

"We had our own language of love, of beauty," she says. "We had ways that we took care of our health and our environment. We had prosperity, union, respect, intellect."

A total of 50 objects have been posted on social media - alongside information about their significance and purpose that shows that women were often at the heart of a society's belief systems and understanding of the natural world.

The images of the objects are presented inside a frame - playing on the idea that a surround can influence how you look at and perceive a picture. In the same way that British colonialism distorted Zambian histories - through the systematic silencing and destruction of local wisdom and practices.

The Frame project is using social media to push back against the still-common idea that African societies did not have their own knowledge systems.

The objects were mostly collected during the colonial era and kept in storage in museums all over the world, including Sweden - where the journey for this current social media project began in 2019.

Yonga was visiting the capital, Stockholm, and a friend suggested that she meet Michael Barrett, one of the curators of the National Museums of World Cultures in Sweden.

She did - and when he asked her what country she was from, Yonga was surprised to hear him say that the museum had a lot of Zambian artefacts.

"It really blew my mind, so I asked: 'How come a country that did not have a colonial past in Zambia had so many artefacts from Zambia in its collection?'"

In the 19th and early 20th Centuries Swedish explorers, ethnographers and botanists would pay to travel on British ships to Cape Town and then make their way inland by rail and foot.

There are close to 650 Zambian cultural objects in the museum, collected over the course of a century - as well as about 300 historical photographs.

Women’s History Museum Zambia

Women’s History Museum Zambia

Mulenga Kapwepwe looks at one of 20 pristine leather cloaks in the Swedish archive collected during an expedition between 1911 and 1912

When Yonga and her virtual museum co-founder Mulenga Kapwepwe explored the archives, they were astonished to find the Swedish collectors had travelled far and wide - some of the artefacts come from areas of Zambia that are still remote and hard to reach.

The collection includes reed fishing baskets, ceremonial masks, pots, a waist belt of cowry shells - and 20 leather cloaks in pristine condition collected during a 1911-1912 expedition.

They are made from the skin of a lechwe antelope by the Batwa men and worn by the women or used by the women to protect their babies from the elements.

On the fur outside are "geometric patterns, meticulously, delicately and beautifully designed", Yonga says.

There are pictures of the women wearing the cloaks, and a 300-page notebook written by the person who brought the cloaks to Sweden - ethnographer Eric Van Rosen.

He also drew illustrations showing how the cloaks were designed and took photographs of women wearing the cloaks in different ways.

"He took great pains to show the cloak being designed, all the angles and the tools that were used, and [the] geography and location of the region where it came from."

The Swedish museum had not done any research on the cloaks - and the National Museums Board of Zambia was not even aware they existed.

So Yonga and Kapwepwe went to find out more from the community in the Bengweulu region in north-east of the country where the cloaks came from.

"There's no memory of it," says Yonga. "Everybody who held that knowledge of creating that particular textile - that leather cloak - or understood that history was no longer there.

"So it only existed in this frozen time, in this Swedish museum."

Women’s History Museum Zambia

Women’s History Museum Zambia

The Swedish collection includes 300 historical photographs, including this one of women wearing leather cloaks

One of Yonga's personal favourites in the Frame project is Sona or Tusona, an ancient, sophisticated and now rarely used writing system.

It comes from the Chokwe, Luchazi and Luvale people, who live in the borderlands of Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Yonga's own north-western region of Zambia.

Geometric patterns were made in the sand, on cloth and on people's bodies. Or carved into furniture, wooden masks used in the Makishi ancestral masquerade - and a wooden box used to store tools when people were out hunting.

The patterns and symbols carry mathematical principles, references to the cosmos, messages about nature and the environment - as well as instructions on community life.

The original custodians and teachers of Sona were women - and there are still community elders alive who remember how it works.

They are a huge source of knowledge for Yonga's ongoing corroboration of research done on Sona by scholars like Marcus Matthe and Paulus Gerdes.

"Sona's been one of the most popular social media posts - with people expressing surprise and huge excitement, exclaiming: 'Like, what, what? How is this possible?'"

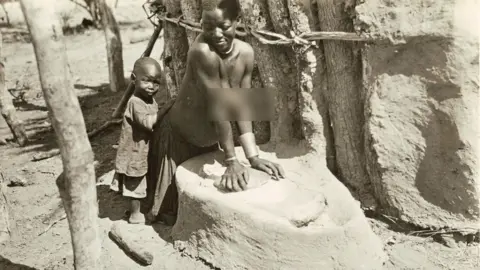

The Queens in Code: Symbols of Women's Power post includes a photograph of a woman from the Tonga community in southern Zambia.

She has her hands on a mealie grinder, a stone used to grind grain.

National Museums of World Cultures

National Museums of World Cultures

This archive photo shows a grinding stone used by Tonga women that would go on to used as a gravestone

Researchers from the Women's History Museum of Zambia discovered during a field trip that the grinding stone was more than just a kitchen tool.

It belonged only to the woman who used it - it was not passed down to her daughters. Instead, it was placed on her grave as a tombstone out of respect for the contribution the woman had made to the community's food security.

"What might look like just a grinding stone is in fact a symbol of women's power," Yonga says.

The Women's History Museum of Zambia was set up in 2016 to document and archive women's histories and indigenous knowledge.

It is conducting research in communities and creating an online archive of items that have been taken out of Zambia.

"We're trying to put together a jigsaw without even having all the pieces yet - we're on a treasure hunt."

A treasure hunt that has changed Yonga's life - in a way that she hopes the Frame social media project will also do for other people.

"Having a sense of my community and understanding the context of who I am historically, politically, socially, emotionally - that has changed the way I interact in the world."

Penny Dale is a freelance journalist, podcast and documentary-maker based in London

More BBC stories on Zambia:

Getty Images/BBC

Getty Images/BBC

1 hour ago

2

1 hour ago

2

English (US) ·

English (US) ·